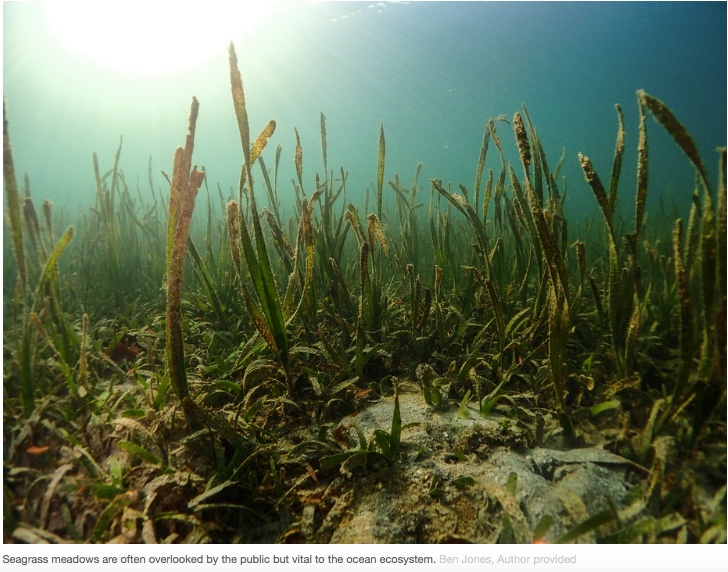

Seagrass has been around since dinosaurs roamed the earth (Note 1), it is responsible for keeping the world’s coastlines clean and healthy, and supports many different species of animal, including humans. And yet, it is often overlooked, regarded as merely an innocuous feature of the ocean.

But the fact is that this plant is vital – and it is for that reason that the World Seagrass Association has issued a consensus statement, signed by 115 scientists from 25 countries, stating that these important ecosystems can no longer be ignored on the conservation agenda. Note 2. Seagrass is part of a marginalised ecosystem that must be increasingly managed, protected and monitored – and needs urgent attention now.

Seagrass meadows are of fundamental importance to human life. Note 3. They exist on the coastal fringes of almost every continent on earth, where seagrass and its associated biodiversity supports fisheries’ productivity. These flowering plants are the powerhouses of the sea, creating life in otherwise unproductive muddy environments. The meadows they form stabilise sediments, filter vast quantities of nutrients and provide one of the planet’s most efficient oceanic stores of carbon. Note 4.

But the habitat seagrasses create is suffering due to the impact of humans: poor water quality, coastal development, boating and destructive fishing are all resulting in seagrass loss and degradation. This leads in turn to the loss of most of the fish and invertebrate populations that the meadows support. The green turtle, dugong and species of seahorse, for example, all rely on seagrass for food and shelter, and loss endangers their viability. The plants are important fish nurseries and key fishing grounds. Losing them puts the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people at risk too, and exposes them to increasing levels of poverty.

Rapid loss

There is clear, extensive evidence of the rapid loss of seagrass. Note 5. Growing historic, recent and current records show degradation and fragmentation of the plant around the world. In Biscayne Bay, Florida, for example, 2.6km² of seagrass disappeared between 1938 and 2009. Note 6. Up to 38% of the seagrass in a lagoon in the south of France may have been lost since the 1920s. Note 7. The nearshore waters of Singapore has lost some 45% over the past 50 years. Note 8. Similar examples have been reported in Canada (Note 9), the British Isles (Note 10) and the Caribbean too (Note 11).

Even the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park has suffered periods of widespread decline (Note 12) and loss of seagrass over the past decade, particularly along its central and southern developed coasts; a consequence of multiple years of above average rainfall, poor water quality, and climate-related impacts followed by extreme weather events. The most recent published monitoring surveys show that the majority of inshore seagrass meadows across the reef – which cover some 3,063 km² – remain in a vulnerable state, with weak resistance, low abundance and a low capacity to recover. Note 13.

Human impact

As the human population grows and the world economy expands, there will be increasing pressure on our coastal zone. And it must be ensured that this doesn’t negatively influence seagrass meadows. It is already recognised that poor water quality, specifically elevated nutrients, is the biggest threat to seagrasses (Note 14); these problems are particularly acute in many developing nations with rapidly growing economies, such as Indonesia, where municipal infrastructure is often limited and environmental legislation is largely weak.

Coastal development is a competition for finite space: boating, tourism, aquaculture, ports, energy projects and housing are all placing pressures on seagrass survival. These threats exist with a backdrop of the impacts of environmental change and sea level rise too. Humans must reduce their local-scale impact on seagrass so that it can remain resilient to longer term environmental stressors.

There can be a bright future for this oceanic plant, however. Across the world, communities, NGOs and governments are beginning to embrace the monitoring of meadows. As knowledge of the plants’ ecology improves, conservationists are learning more about how to successfully restore seagrass meadows: Tampa Bay in Florida (Note 15) and Virginia’s bays (Note 16), for example, have seen genuine large scale recovery. We also now have greater appreciation for the value of seagrass in the global carbon cycle, and governments are more willing to include its conservation in ways to mitigate carbon emissions. Though commendable, these are just the first steps on a course of targeted strategic action.

As the WSA statement calls, seagrass meadows must be put at the forefront of marine conservation today. (see Note 2). We need to increase its resilience by improving coastal water quality, prevent damage from destructive fishing practices and boating, include seagrasses in Marine Protected Areas and ensure that fisheries aren’t over exploited. Note 17. Seagrasses also need to be managed effectively during coastal developments, and steps taken to ensure recovery and restoration in areas where losses have occurred.

The scientific community must be more united, not only in its work, but in engaging more actively with the general public, coastal managers and conservation agencies too. Seagrass ecosystems must fully pervade policy around the globe too, as well as the consciousness of our global coastal communities. For the sake of future generations we need to work together to ensure the survival of the world’s seagrass meadows now.

Notes:

1.SeagrassWatch, “What is seagrass?” www.seagrasswatch.org/seagrass.html

2. World Seagrass Association wsa.seagrassonline.org. The Consensus statement from the World Seagrass Association is found at wsa.seagrassonline.org/securing-a-future-for-seagrass/; list of signatories at wsa.seagrassonline.org/securing-a-future-for-seagrass-signatories/

3. Richard K.F. Unsworth, “For the love of cod, let’s save our disappearing seagrass,” The Conversation (29 Oct 2014). theconversation.com/for-the-love-of-cod-lets-save-our-disappearing-seagrass-33196

4. Paul Lavery, “Seagrass is a huge carbon store, but will government value it?”, The Conversation (5 Sept 2013). theconversation.com/seagrass-is-a-huge-carbon-store-but-will-government-value-it-17878

5. Michelle Waycott, et al., “Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) (29 July 2009). www.pnas.org/content/106/30/12377.full.pdf

6. Rolando O. Santos, Diego Lirman, Simon J. Pittman, “Long-term spatial dynamics in vegetated seascapes: fragmentation and habitat loss in a human-impacted subtropical lagoon,” Marine Ecology (Feb 2016). onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/maec.12259/abstract;jsessionid=7DB0F785158BADF7FBB7B9D799AA24B9.f01t01

7. F. Holon, P. Boissery, A. Guilbert, E. Freschet, J. Deter, “The impact of 85 years of coastal development on shallow seagrass beds (Posidonia oceanica L. (Delile)) in South Eastern France: A slow but steady loss without recovery,” Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science (Nov 2015). www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272771415001663

8. Siti Maryam Yaakub, Len J. McKenzie, Paul L.A. Erftemeijer, Tjeerd Bouma, Peter A. Todd, “Courage under fire: Seagrass persistence adjacent to a highly urbanised city–state,” Marine Pollution Bulletin (2014). research.jcu.edu.au/tropwater/publications/Courageunderfireseagrasspersistence.pdf

9. K. Matheson et al., “Linking eelgrass decline and impacts on associated fish communities to European green crab Carcinus maenas invasion,” Marine Ecology Progress Series (2016). www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v548/p31-45/

10. Benjamin L. Jones and Richard K. F. Unsworth, “The perilous state of seagrass in the British Isles,” Royal Society Open Science (2016). rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/royopensci/3/1/150596.full.pdf

11. Brigitta I. van Tussenbroek “Caribbean-Wide, Long-Term Study of Seagrass Beds Reveals Local Variations, Shifts in Community Structure and Occasional Collapse,” PLOS/ONE (3 March 2014). journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0090600

12. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), Australia, A Vulnerability Assessment for the Great Barrier Reef (Information valid as of Feb 2012). www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/21743/VA-Seagrass-31-7-12.pdf

13. L.J. McKenzie et al., “Marine Monitoring Program: Inshore seagrass, annual report for the sampling period 1st June 2013 – 31st May 2014,” Marine Monitoring Program – Inshore Seagrass, GBRMPA (2015) elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/handle/11017/2976

14. Alana Grech et al., “A comparison of threats, vulnerabilities and management approaches in global seagrass bioregions,” Environmental Research Letters, (12 April 2012). iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326

15. Craig Pittman, “Tampa Bay sea grass beds expand, show water is now as clean as it was in 1950,” Tampa Bay Times (13 May 21015). www.tampabay.com/news/environment/water/tampa-bay-seagrass-beds-expand-show-water-is-now-as-clean-as-it-was-in-1950/2229442

16. Daniel Malmquist, “Eelgrass restoration aids overall recovery of coastal bays,” Virgina Institute of Marine Science (20 Feb 2012). www.vims.edu/research/topics/sav/ts_list/eelgrass_restoration.php

17. Leanne C. Cullen-Unsworth, Richard K.F. Unsworth, “Strategies to enhance the resilience of the world’s seagrass meadows,” Journal of Applied Ecology (24 march 2016). onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.12637/abstract

Authors:

Richard K.F. Unsworth is a director of Project Seagrass and President of the World Seagrass Association.

Jessie Jarvis is affiliated with the World Seagrass Association Inc (Treasurer) and the Atlantic Estuarine Research Society (Treasurer).

Len McKenzie receives funding from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. He is affiliated with the World Seagrass Association (Secretary) and Seagrass-Watch (Director).

Mike van Keulen is affiliated with the World Seagrass Association (Vice President). He receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation.

Originally published in The Conversation at theconversation.com/seagrass-is-a-marine-powerhouse-so-why-isnt-it-on-the-worlds-conservation-agenda-66503

No comments yet, add your own below