The usage of the term “environmental justice,” and its counterpart, environmental injustice, differs somewhat in the United States and European Union, as we have pointed out in an earlier iePEDIA and in a Report on an EEA study in this magazine. See Sources. In the US, the term refers to a fair distribution of environmental burdens, and benefits, without a disproportionate, negative impact on communities of color or low income. The concept developed in the 1980s and grew out of the civil rights and social justice movement of the 1960s, especially in the African American community. In the EU it generally refers to the principle that all people are entitled to a clean and healthy environment, as a matter of justice. While it is used to describe efforts to protect poor or ethnic marginalized people from environmental harms, it also addesses adverse impacts on wider populations, including global issues and intergenerational conflicts. The US environmental justice community has resisted this wider application because it is seen as a weakening of the focus on behalf of people of color or low income.

Context

In a recent study, the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), the European Roma Grassroots Organisations Network (ERGO) and Environmental Justice, have examined Environmental racism against Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe. The study reviews the racially motivated discrimination and exclusion of persons stimatised as “gypsies,” or antigypsyism. In Ireland, there are travellers, or tinkers, who are alleged by some to be related to the Roma gypsy communities, but the connection is subject to dispute. Whatever their origin, the Irish travelers are subject to much of the same treatment as the Roma gypsies.

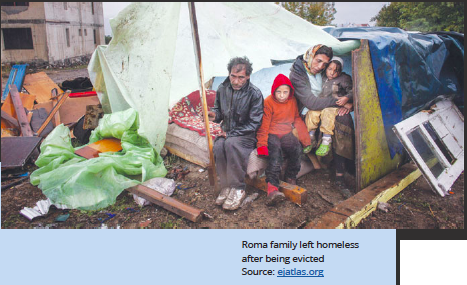

The discrimination, particularly within the EU, the subject of the study, is not surprising but it does bear repeating. Between 10 and 12 million Roma live in Europe, with about 6 million in the EU, forming the region’s largest ethnic minority. “Roma communities have historically experienced social, economic, political and cultural exclusion, spatial segregation and discrimination, but also racially motivated violence such as hate speech and crime, forced evictions, cultural assimilation, coerced sterilisation, and genocide.” At 6. Such ghettoisation has resulted in wide-spread poverty, unemployment, lack of education, and poor health, all of which continue across the EU.

The discrimination, particularly within the EU, the subject of the study, is not surprising but it does bear repeating. Between 10 and 12 million Roma live in Europe, with about 6 million in the EU, forming the region’s largest ethnic minority. “Roma communities have historically experienced social, economic, political and cultural exclusion, spatial segregation and discrimination, but also racially motivated violence such as hate speech and crime, forced evictions, cultural assimilation, coerced sterilisation, and genocide.” At 6. Such ghettoisation has resulted in wide-spread poverty, unemployment, lack of education, and poor health, all of which continue across the EU.

What the current study offers is an analysis of how this marginalization and discrimination is affecting the environment of the Roma community. The Report also presents the analysis of 32 cases of environmental racism against Roma communities identified in Bulgaria, Slovakia, Romania, Hungary, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Kosovo.

Environmental Impacts

The spatial segregation of Roma communities pushes them to the outskirts of smaller towns, isolated villages, or urban or semi-urban ghettoes. Such places lack the basic public environmental services, including clean and safe water, sanitation and trash collection. These services are usually available for nearby communities.

· In Slovakia, only 61% of those living in the 100 biggest Roma communities have access to potable water in their homes.

And the marginal spaces often are already polluted or contaminated, such as landfills, toxic industrial sites, abandoned mines, or areas subject to flooding. Even when the Roma communities are able to locate to less desolate or polluted areas, they often find themselves evicted so that more economically productive uses can be made of these sites.

· Research has shown that around half of Romanian Roma live close to waste dumps (At 10).

· Scientific research has covered several cases in North Macedonia where Roma were forcibly evicted to live near heavily polluted industrial sites (At 11).

· In Romania, a Black Sea holiday resort became the scene of drastic and unlawful action by the local municipality in 2013 against more than 100 Roma, including 55 children, living in the area. The Roma had been living in this area for more than 40 years, nevertheless, their homes were demolished without consultation or provisions being made for alternative housing (At 31) .

At the same time, the Roma communities lack information, knowledge or resources for access to legal systems that might protect their rights. Clearly, the right to a healthy environment is enshrined in constitutions and other laws across EU member states. Protections in the Aarhus Convention and Sustainable Development Goals are unknown or unavailable to most Roma communities.

· Reports highlight cases of racial discrimination and racial profiling against Roma without any attempt to investigate those cases by independent bodies (At 10).

These social and environmental living conditions expose the Roma communities to wide-spread adverse health effects. The study reports that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has shown that almost one fourth of all deaths globally are related to environmental risks.

· The Regional Office of Public Health in Slovakia in 2008 reported that the life expectancy of Roma is estimated to be 10-15 years lower than that of the overall population (at 7); Roma men have a life expectancy of approximately 10 years lower and Roma women of approximately 18 years lower than non-Roma Hungarians (at 8).

Certainly we are seeing the disproportionate impact from the coronavirus on poor, vulnerable communities, as much as on vulnerable populations of older citizens. The Roma communities, for instance, have limited access to clean water for washing their hands as frequently as is recommended. And if they do get sick from the virus, they have little, if any, health care available to them.

· In Bulgaria, for example, authorities have imposed special virus measures on Roma communities, including checkpoints outside Roma ghettos

· Studies on access to health services show that Roma often do not have health insurance (45–48% are insured compared to 85% of the general population) (At 9).

Conclusion

In light of these continuing prejudices against Roma, including environmental injustices, the report proposes a series of policy recommendations across EU and Member States laws to better protect the Roma communities.

The Report makes a timely contribution to our understanding of how vulnerable communities, such as the Roma, remain at serious risk from environmental assaults. As soon as the coronavirus crisis recedes (assuming it does), the fast unfolding impacts from climate breakdown will resurface.

And who is going to protect these vulnerable communities and populations from climate breakdown, a threat far more dangerous, far-reaching and longer-lasting than the coronavirus crisis.

Sources:

Heidegger, P.; and Wiese, K. (2020). Pushed to the wastelands: Environmental racism against Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe. Brussels: European Environmental Bureau bit.ly/35xL2Jb

EEA, “Unequal Impacts From Air and Noise Pollution, and Extreme Temperatures, on Vulnerable Populations,” in Reports section of irish environment (1 March 2019). bit.ly/2zGXgTO

“Environmental Justice,” in iePEDIA section of irish environment (1 April 2018). bit.ly/2xigONo

Kate Phelan, “A Brief History of Irish Travellers, Ireland’s Only Indigenous Minority,” culture trip (16 March 2017). bit.ly/3cW2c5u

No comments yet, add your own below