Introduction

Economics, and economists, tend to dominate much of the conversation about environmental matters these days, like toxicologists did thirty years ago. This is neither good nor bad, it just is.

Over the past several decades there have been more and more attempts to put a price on nature, or biodiversity, or natural capital. The impulse derives from a sense that in order to preserve nature, it has to be valued, or monetised. No value, no need to protect it. It’s like putting a price on yourself, defining your value in Euros, which is a difficult task but sometimes useful, sometimes even necessary.

If businesses continue to exploit our common natural resources, such as water, air, biodiversity, then we need to make them pay us for that exploitation. But first we have to figure out how to put a value on these resources. The instant report, Natural Capital at Risk: The Top 100 Externalities of Business, produced by Trucost for The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), is another effort to develop the methodology and substance for putting a value on natural resources.

The Report

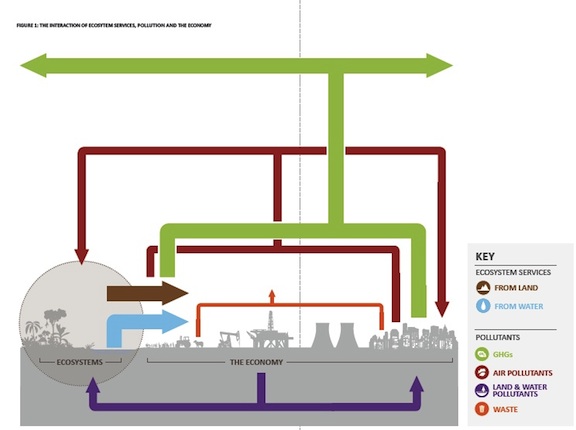

The consultants have estimated in dollars the financial risks from companies not accounting for the natural capital, or resources, that they use in their operations and productions, and the consequences if and when those costs become internalized. The analysis is based on modeling that maps the flow of inputs and environmental impacts through an economy, also known as an environmentally extended input-output model (EEIO). The modeling was applied to various business sectors at sub-continental regional levels, as defined by the United Nations.

Natural capital assets include those that are non-renewable and traded, such as fossil fuels and minerals, also called commodities, and those renewable goods and services which generally are not priced, such as clean air, groundwater and biodiversity. The major unpriced natural capital assets considered are: water use, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, waste, air pollution, land and water pollution, and land use.

The overall conclusion is “that some business activities do not generate sufficient profit to cover their natural resource use and pollution costs.” At 7. These businesses are in effect getting a free ride from society; the polluters are not paying their full share.

As an example, carbon dioxide (CO2) allowances under the EU Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) were trading at less than €4 ($6) per metric ton at the time of the report, whereas the social cost for CO2 was estimated at US $106/ton, based on the Stern Report. In addition, fossil fuel subsidies in OECD countries were estimated at US $55 billion annually. At 18. All of this constitutes a permit to pollute.

The report breaks down the analyses by region and sectors and by environmental impact. It is acknowledged that there is significant variation between countries and within sectors, but an overall picture reveals disturbing trends.

When the region and sectors are ranked by highest natural capital cost, the top five include coal power generation in Eastern Asia and Northern America. Interestingly, in an article on the recent Joint US-China Statement on Climate Change, which Statement provided for little concrete action, staff at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) argued that one concrete action that China and the US could take would be to curb carbon emissions from the power sector. China’s power sector accounts for about 50% of its coal consumption and emissions, while the emissions from existing US coal-fired power plants are still the largest source of carbon pollution, even though the power sector has recently reduced its reliance on coal.

Also included in the top five are farming in South America and Southern Asia where water is scarce and high production levels require high land use. When the natural capital costs are compared to the revenue generated by sectors in various regions, in each case the top five incur natural capital costs in excess of revenue. For instance, “cattle ranching and farming” in South America runs up costs of $353.8 billion but has revenues of only $16.6 billion. As the report notes, “The extent to which agricultural sectors globally do not generate enough revenue to cover their environmental damage is particularly striking from a risk perspective.” At 9.

Of course, this applies only if and after natural capital costs are included in the cost of doing business, i.e., after they are internalized. While there is not yet widespread internalization of natural asset costs, there are occasions when such costs do factor into prices, such as when a drought recently hit the US agriculture sector causing prices to rise.

If unpriced natural capital costs are internalized, the report concludes that a large portion of these costs would be passed on to consumers. Consumers could or would turn to other products, which did not require such heavy natural capital costs, for example those that had developed their business on renewable energy.

One of the advantages of the report is that the identification of risks associated with a heavy reliance on unpriced natural assets provides opportunities for companies, and investors, to adjust their behaviors – the companies to turn to less intensive production and the investors to focus their money on less polluting and less risky businesses. As the report concludes, “… those companies that align business models with the sustainable use of natural capital on which they depend should achieve competitive advantage from greater resilience, reduced costs and improved security of supply.” At 12.

Investors beware.

Conclusion

This report for TEEB is one of several recent efforts to highlight the costs of natural resource uses, and overuse, and pollution of those resources. In a comparable vein, Lord Stern’s economic analysis of the costs of mitigation and adaptation from global climate change reaches the same issue – what it is costing us to destroy natural assets.

Recent studies have also focused on the dangers of a so-called carbon bubble. Fossil fuel companies include in their valuation of their stocks the amount of reserves of oil and gas that they own, but have not yet developed. But the argument is being made that these reserves must be left in the ground or seas if we are to avoid the catastrophic climate changes that are heading our way. We have just exceeded a daily level of 400 ppm of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and that well may head us in the direction of a 5º C increase in global temperatures. If the fossil fuel companies cannot extract and burn those reserves —— so-called unburnable carbon — then their company is worth less. If they have to pay for use of natural resources, they will have to pass those costs along to customers or go out of business. And if someone else has figured out how to produce the same thing by relying on renewable energy and less water and land, then the fossil fuel companies will be driven out of business.

As another example, recently there has been some consideration by the Irish government to sell the harvesting rights of the State forestry company Ciollte. The argument has been made that any buyers of Irish forest should have to pay for lost recreational uses as well as for the wood they harvest. If they do not pay for that lost recreation, the State would have to continue to provide these benefits and this could mean the Exchequer would be the loser in the long term.

Understanding the economic risks from natural resources depletion, along with the climate impacts, is obviously critical. Yet the very act of putting a price on natural capital carries its own risks, as George Monbiot and others have argued. If nature has to be priced in order to preserve it, if it is commodified, then it may become subject to the laws of the market place. If nature is priced, then can it be bought and sold and discarded at the whim of those with the most money. Such conditions differ markedly from considering nature as a public good the use of which is determined by public interests, not private economic motives.

Sources:

Natural Capital At Risk: The Top 100 Externalities Of Business, undertaken by Trucost on behalf of The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (April 2013). www.teebtest.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/2013-Natural-Capital-Risk-The-Top-100-Externalities-of-Business.pdf

Jake Schmidt and Barbara Finamore, “Are China and the US finally getting serious about climate change?” chinadialogue (07 May 2013). www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/5988-Are-China-and-the-US-finally-getting-serious-about-climate-change-

Sir Nicholas Stern, Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, HM Treasury webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/sternreview_index.htm

Carbon Tracker Initiative, Unburnable Carbon – Are the world’s financial markets carrying a carbon bubble? www.carbontracker.org/carbonbubble

“Public access to forests raised as part of growing opposition to sale of Coillte Rights.” www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/public-access-to-forests-raised-as-part-of-growing-opposition-to-sale-of-coillte-rights-1.1385562

George Monbiot, “Putting a price on the rivers and rain diminishes us all: Payments for ‘ecosystem services’ look like the prelude to the greatest privatisation since enclosure,” The Guardian (06 August 2012). m.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/aug/06/price-rivers-rain-greatest-privatisation?cat=commentisfree&type=article

George Monbiot, “The Self-Hating State: Devolving policy to ‘the market’ doesn’t solve the problem of power. It makes it worse.” The Guardian 23 April 2013. For fully annotated version see: www.monbiot.com/2013/04/22/the-self-hating-state/

No comments yet, add your own below