Introduction

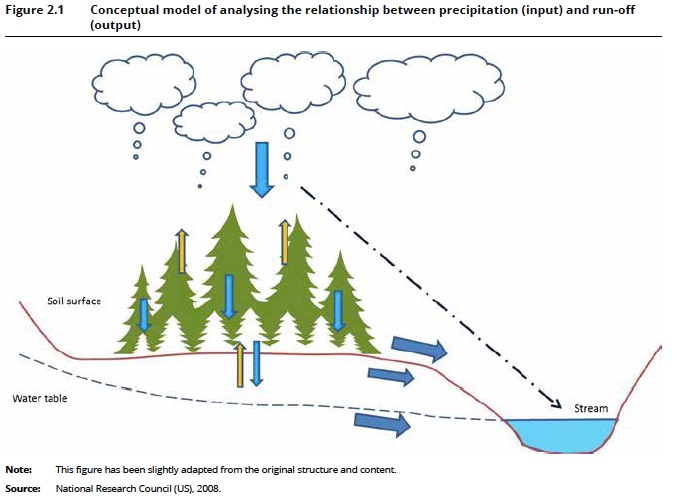

The celebration of the beauty and usefulness of trees in Joyce Kilmer’s poem, however sentimental, offers a poetic vision matched by a scientific assessment from the European Environment Agency on how forests can help prevent floods and droughts. The report is Water-retention potential of Europe’s forests: A European overview to support natural water-retention measures. Certainly one of the clearest consequences of global climate change is and will be the increase in flooding and, seemingly paradoxical, droughts and the report analyzes the ways in which forest cover can lessen the impacts. Forests retain excess rainwater reducing run-off, which in turn helps to minimize flooding, and releasing water in the dry season to help reduce the effects of droughts.

About 1/3 of the European territory (210 million hectares or about 519 million acres) is covered by forests. Ireland has the lowest forest cover of all European countries, approximately 11%, and these forests are mostly man-made. The UK is not much more forested with 13% woodland cover (Forestry Commission 2011), and Northern Ireland has about 6.5%.

Context

We should first understand the possibilities and limitations of the EEA report. It provides for the first time a European overview of the role of forests in water retention. The data represent 287 sub-basins with more than 65,000 catchments across Europe, including only sub-basins with more that 10% forest cover. But the available data varies widely from country to country and so comparisons are difficult. In addition, forest hydrology is complicated and dependent on a number of factors, such as water yield and water quality, which are subject to debates amongst the experts. Also, retention is dependent on factors such as length of growing season, tree density and number of layers of vegetation cover.

Nevertheless, the report serves as a preliminary assessment of the importance of forest cover on water retention. It does so by focusing on 3 factors: forest cover, measured in hectares; forest types (coniferous, broad-leaved, mixed); and the degree of management of the forests (protected vs. commercial forests).

The report defines “water retention” as “water absorbed or used by forests.” And “forests” are defined as land of more that 0.5 hectare (1.2 acres) with trees higher than 5 meters (16 feet) and a canopy cover of more than 10%, or trees able to reach these thresholds in situ.

Results

Not surprisingly, the more forest cover available, the more water retention potential exists for most areas. For areas of 30% to 70% forest cover, water retention is 25% to 50% higher, respectively, than areas with only 10% cover. Yet in dry Mediterranean sub-basins, because of the soil conditions there, run-off actually increases with more forest cover.

Seasonal changes affect water retention with retention 25% greater in summer than in winter. This may have important consequences for planning in a place like Ireland where models predict more rain in winter and less in summer. But, interestingly, when forest cover exceeds 30% of the sub-basin area, the forests affect run-off regardless of the season.

The type of forest also affects retention, although not greatly, with coniferous forests generally promoting retention of 10% more water than broadleaved or mixed forests. Finally, it was found that Alpine and Continental regions generally have higher water retention potential than Atlantic and Mediterranean regions, although there is insufficient data in Mediterranean regions to attribute this to forest cover.

The report could not identify any conclusions about water retention related to the impact of the management of forests.

The EEA also reviews current efforts for EU Natural Water-Retention Measures, such as the obvious growing of forests, as well as restoring wetlands and lakes, removing dams and reducing tillage in agriculture. Other EU strategies and policies, such as the Biodiversity Strategy to 2002 and Forest Strategy, are applied to the challenge of promoting water retention.

Conclusion

The report is careful to point out the limited data available for many regions and the complexity of factors that affect water retention. As it concludes, the results are highly aggregated and generic and do not provide any easy set of measures that can be directly implemented at the local scale. But as water scarcity becomes a more menacing problem across the EU, and world, anything that helps us to understand how to retain water is important.

It is also important to remember, as the report does, that water retention is not the only ecosystem function provided by forests and the biodiversity values of forests have to be considered in designing any Natural Water Retention Measure.

Sources

European Environment Agency, Water-retention potential of Europe’s forests: A European overview to support natural water-retention measures (September 2015). www.eea.europa.eu/publications/water-retention-potential-of-forests

Teagasc: Agriculture and Food Development Authority, A Brief Overview of Forestry in Ireland (11 March 2015). www.teagasc.ie/forestry/advice/forestry_history.asp

Woodland Trust, The State of the UK’s Forests, Woods and Trees: Perspectives from the sector (2011). www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/mediafile/100229275/stake-of-uk-forest-report.pdf?cb=58d97f320cab43d78739766e71084f76

No comments yet, add your own below