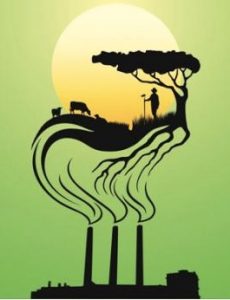

Agriculture has been hiding in the grasses to avoid dealing with climate change

Pressure is mounting for action, finally

We have written recently about how the conversation about agriculture’s responsibility for the growth of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in Ireland has changed. That shift in the conversation is now increasingly happening across the globe following the Paris climate agreement.

Agriculture has been given a free pass by the Irish government to avoid reducing GHGs, particularly methane, at the same time that the government is expanding the sector and is behind in its obligations under EU law to reduce GHGs. Various rationales have been advanced by the industry-government to justify this privileged position, as embodied in their joint policy called Harvest 2020 and Food Wise 2025. A leading rationale was that Irish food products were necessary to save the poor and starving populations around the world. Of course this has been roundly debunked. As we noted:

The food being produced, and promoted, by the Irish agri-food-government complex is upscale beef and cheese and milk that is exported primarily to the UK and EU and other international markets. Irish food products are not going to feed the growing masses in developing countries who are underfed or even starving, but rather are going to contribute to more obesity for the world’s well-off. So the populations in the developing countries, where growth will happen, do not need Ireland’s food products, and cannot afford them. See Report on Climate Smart Agriculture in irish environment magazine (below in Sources).

The report itself, Climate Smart Agriculture, acknowledged that, “At its heart, however, [Food Wise 2025] is a plan to increase food output in the period to 2030, which would result in an increase in absolute gross levels of greenhouse gas emissions.” At 38. This report was issued by the Institute of International and European Affairs (IIEA) and the Royal Dublin Society (RDS) (July 2016).

Around the same time, a group of environmental Non Government Organisations (eNGOs) issued a response to the IIEA/RDS report reinforcing the fallacy of the rationale. See Report on Climate Smart Agriculture.

In addition to the “we-need-to-feed-the-poor-and-starving” rationale, the industry-government has argued that the agriculture sector in Ireland can move toward a “carbon neutrality” through carbon sequestration by grassland soils and forestry, arguably reducing its GHGs. Again the IIEA/RDS and eNGO reports demonstrate that such options are far fetched. “Carbon neutrality” is not even well defined. The alleged efficiency measures to get there, wherever “there” is, are merely theories or lab experiments with little proven implementation, or any interest by farmers to adopt such measures. And expansion of forestry is wishful thinking as Ireland has one of the lowest levels of forest cover in the EU, at 11%, and the goals of increasing forest cover would require planting 16,000 hectares per year yet the government’s target remains at 7,300 hectares per year. Moreover, the discussion always talks about carbon, ignoring entirely methane, the GHG with the highest emission levels from agriculture.

Finally, recent research reports from Teagasc, the Irish government’s Agriculture and Food Development Authority, acknowledge that the government’s agriculture targets and policies are not compatible with climate change obligations. In one report, it analysed the possibilities of mitigation from managing soil functions, including carbon sequestration. It accepted that such efforts were unlikely to offset the emissions from an expanded agriculture sector. Clearly something has to give: either an uncontrolled expansion of agriculture or Ireland’s legal obligations to reduce GHGs.

This new-found realism about agriculture’s responsibilities for climate change in Ireland is reflected and reinforced by global efforts to deal with the obligations embodied in the Paris climate agreement of December 2016. As an article by Georgina Gustin in inside climate news demonstrates: “After years of being off the table in climate talks, agriculture is now being considered widely by countries trying to reach their Paris emissions cuts pledges.”

The commitments at Paris, while voluntary, have been taken seriously by most, not including President T-Rex in America.

Over 80% of countries indicated they would use agricultural practices to curb GHGs, as well as related practices in forestry and land use. Confirming this focus, at the Marrakech meetings to start the process of implementing the Paris agreement, there were at least 80 agriculture-focused sessions. One environmentalist argued that as agriculture accounts for 13% of GHGs it is surprising that it has taken so long for the focus to land there. Since in Ireland agriculture accounts for about 33% of GHG emissions, the delay is all the more surprising.

Gustin points out that in the first global climate summit, in 1992, agriculture hardly mattered. Over the past decade research on agriculture has intensified, but even here the emphasis was on the effects of deforestation and land use rather than specifically on agriculture. While efforts have created mitigation strategies and measures for forestry, the same cannot be said about agriculture.

Agriculture has always been a sensitive area as it implicates food supplies and rural life in most countries. At the same time, the farming community is recognizing that they are being adversely impacted by climate change with flooding, drought, lower pollination, and invasive species, and that mitigation, from whatever sector, serves their interests.

The focus on agriculture’s responsibilities globally will only further expose the privileged position that agriculture has enjoyed in Ireland. That privilege may be short-lived.

While much needs to be done to figure out exactly how farming practices can be modified to help reduce GHGs, and preserve farming as a viable livelihood, certainly in Ireland it is about time that the government convened a public consultation on the matter. If the expansion of the agriculture sector is going to continue, then the sector has to contribute its fair share of efforts to significantly reduce GHGs, or the government needs to identify who else is going to make sacrifices. The IT industry? All drivers? Or all taxpayers because the government chooses to pay massive fines for failing to meet its GHG-reduction obligations?

Sources:

Georgina Custin, “2017: Agriculture Begins to Tackle Its Role in Climate Change” inside climate news (4 Jan 2017). insideclimatenews.org/news/03012017/agriculture-climate-change-paris-agreement-global-warming-drought

“Climate Smart Agriculture: If Only. Reports from IIEA/RDS, and from Environmental Pillar/Stop Climate Chaos,” in Reports section of irish environment magazine (September 2016).

Kristine Valujeva, Lilian O’Sullivan, Carsten Gutzler, Reamonn Fealy, Rogier P.O. Schulte, “The challenge of managing soil functions at multiple scales: An optimisation study of the synergistic and antagonistic trade-offs between soil functions in Ireland,” Land Use Policy (15 Dec 2016). www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837716300205

Interview with Dr. Cara Augustenborg in Podcast section of irish environment magazine (February 2017).

“Carbon Neutral” in iePEDIA section of irish environment magazine (January 2017). www.irishenvironment.com/iepedia/carbon-neutral/

No comments yet, add your own below