40 years ago a cloud of dioxin descended on Seveso, Italy

In July 1976, some 40 years ago, weather was, as usual, hot and sticky in Seveso, Italy. But it was an explosion–a loud, screeching, hissing sound—at a nearby chemical plant that caught the attention of the residents of Seveso and Meda. As they turned toward the sound, they saw the cloud, varyingly white and gray, heading toward and then over them. The cloud descended on them, like a fog filled with damp crystals. The fallout caused coughing and burning eyes, quickly followed by headaches, dizziness, and diarrhea. The people were accustomed to smoke and pollution from the surrounding industries, and therefore were not alarmed initially. As one resident stated, “At that time, we didn’t pay much attention to it, because there was always some cloud, some leak. And although there was a terrible smell, we didn’t worry about it; we ate, we collected vegetables and flowers from the garden, as if nothing had happened.”

The northerly wind pushed the cloud south, covering an area four miles long and a third of a mile wide within half an hour. The chemicals in the cloud dispersed over the area, hitting Seveso the hardest, but also spreading over parts of seven nearby towns, including Meda, Desio, and Cesano Maderno.

People were told by the chemical company and local authorities only that the explosion contained some toxic substances but there was nothing to worry about. So everyone carried on their normal routines outdoors, including eating produce from their gardens. Imagining that the contaminated air carried substantial risks for them and their children was perhaps too difficult. But then birds died, rabbits sickened, and children developed horrible pustules and other skin deformities.

Only several weeks later did the company acknowledge that the toxic substance was dioxin, one of the most toxic substances. Then with little warning, the authorities ordered everybody to evacuate with only the clothes on their backs and a suitcase. Some resisted and tried to bring their pets, but the authorities stopped them and the pets were forced to stay behind.

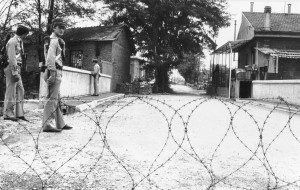

Most of the evacuees had built their homes in their spare time, either by themselves or with the help of relatives and neighbors. Most had a garden, even a small farm, attached to the house, where they grew vegetables, kept chickens, rabbits (ragout was a favorite dish), ducks, and goats, and tended peach, plum, apricot, and pear trees, all for their own subsistence. Now all of this was taken from them. The area — which became known as the Zone — was cordoned off with barbed wire fencing, nine feet high and some six miles long, and was guarded by armed soldiers. The pets in the Zone were destroyed.

All of this paled in comparison to the sight of their children’s faces, swollen with pustules and running sores, ridden with black and scarlet pockmarks. The children were taken away and put in camps during the day, to protect them from the dangers in the Zone. Despite protests by the authorities, a number of pregnant women had abortions rather than risk giving birth to newborns with serious deformities because of exposure in the Zone. Their lives had become, as they said, bruttissima, the ugliest kind of life.

Very soon after the boundaries for relocating residents were established, further sampling results indicated that the area of risk was much wider and the boundaries had to be expanded.

No one could tell them how long they would be relocated, nor even if they would be returning to their homes, or whether their homes would even be there. They had to live in crowded temporary accommodations, along with others who were suffering from similar illnesses and deep anxieties. When they ventured out from this group, they were treated as contaminated themselves. Being dislocated from everything that looks, feels, and smells familiar is traumatic. As a Portuguese proverb instructs, “To change one’s habits has the smell of death.”

All these uncertainties were compounded by the questions about long-term, as-yet-to-be-seen consequences of the dioxin exposure. Would their babies be deformed, would they or their children develop cancers in ten, twenty, thirty years? The uncertainty about the effects of environmental disasters can be more debilitating that living through the disastrous event itself, just as waiting to hear the results of our own health tests can produce more anxiety, even downright fear, than the illness itself.

For those who were not relocated and stayed in their homes in “uncontaminated” areas, there was likely some comfort in believing that they were not at risk. That particular certainty was misleading. Some twenty years later, studies suggested that staying in place subjected them to risks of increased disease from the exposure to dioxin.

The anger that followed the explosion, and the way the company and authorities reacted to the explosion, spilled over into vigilantism with attacks on and even killing of company personnel. More rational changes to the legal regime also followed. Italy’s national health care system was reformed, especially with regard to exposures to toxic chemicals. In the international arena, the European Economic Community, now European Union, passed legislation — the Seveso Directive —to control the transnational shipment of toxic wastes. These legal reforms are a way of addressing the anxieties and uncertainties that follow environmental disasters. At least if collective action is taken to address some of the factors that caused the disaster, there is some comfort that other disasters can be avoided. Of course, if no one enforces the tougher laws then the comfort is ephemeral.

Some 40 years later the people exposed to dioxin continue to be subjected to disturbing health effects. The uncertainty that settled on their lives, like the cloud from the factory, remains with them.

Adapted from “Seveso, Italy, 1976,” in Robert Emmet Hernan, This Borrowed Earth: Lessons From the 15 Worst Environmental Disasters Around the World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010; China Machine Press, 2011).

No comments yet, add your own below