Future of cities: we need more living and work spaces

We need fewer cars

Cars are to cities what cows are to the Irish countryside: engines of greenhouse gases (GHGs). Since over a number of years we have covered the intractable problem of GHGs, especially methane, from cows and other animals in the Irish countryside, we thought it was only fair to focus on the intractable problem of cars in cities. Currently across the globe over 50% of people live in urban areas (about 62% in Ireland), and 70% are expected by 2050. And most insist on bringing their car(s) along.

In Ireland, by 2040 there will be more people, many of them older, living in more houses, but with fewer people per house, and with more jobs, mostly high-skilled ones. Importantly, the growth in houses and jobs will be concentrated in cities or urban areas. And Ireland remains a car-dependent society with over 2/3 of commuters driving to work and 1/10 spending one hour or more commuting. That requires a lot of parking facilities and leads to more urban sprawl. And those cars in congested urban areas will generate tons of toxic fumes, increasing the health risks to urban dwellers. So planning for the protection of the air quality in such congested areas is paramount for 2040. See the Report on The Space We Have: Planning for Ireland in 2040 in the May issue of www.irishenvironment.com

For city planning, how do we balance the needs for more living and work spaces for more people in Dublin and other urban areas in Ireland with the need for fewer cars to get from home to work to shop to cultural and recreational activities, and elsewhere.

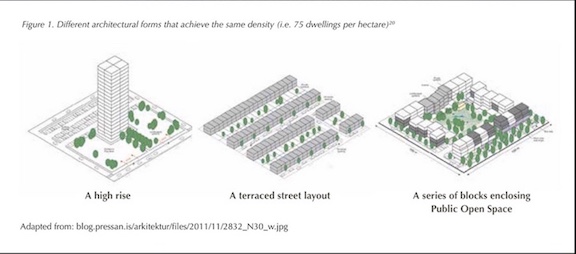

In Ireland much, if not most, of the talk about city planning is dominated by how high should residential and commercial buildings be: 6 stories, or 8, or 12, or more? Of course density does not necessarily mean high-rise residential buildings. It can mean spreading the density out over a horizontal grid with more, lower buildings. Frank McDonald has suggested that if residential buildings were raised to five or six stories, Ireland could reach European-styled densities of 160-200 housing units per hectare. See Comiskey in The Irish Times.

Density and “high” rise are relative terms. In Manhattan New York, the newer residential up-market towers are 65 to 95 floors high; in Dublin a high rise might entail 7 – 10 stories. While such NY high rises would suggest increased density for Manhattan, that’s not a simple equation. For the up-market high-rises are quite large, with several thousand square feet of living space for perhaps 2 – 4 people, so not many people are cramming into these spaces. Moreover, these residences also are not the primary residence for many occupants but often serve as a simple pied-a-terre (at cost of $25 to $90 million, with as high as $5,000 per square foot!), visited occasionally throughout the year.

But density may not be the critical condition that defines whether cities are livable or not; it may be how cars are treated. There are numerous local and national governments around the world planning or implementing ways of reducing the concentration of cars in their cities by restricting their access, or banning them outright, or by taxing or charging them for using the city, or limiting their parking spaces. These are so-called “car-limiting strategies.” But trying to just hide or ban cars may not be enough as people still have to get from place to place within the city. So before banning or restricting cars, it will be necessary to provide the infrastructure and facilities that lessen or eliminate the need for cars.

In a recent blog post in grist, Henry Grabar explores the unavoidable challenge of fighting cars if cities want to honor the Paris Accord and reduce GHGs. As he bluntly states: “Want to fight climate change? You have to fight cars.” In large cities cars account for about a third of GHGs. And an imperative within this fight is to reduce vehicle miles traveled. Which in turn suggests that we have to build residences and businesses close to public transport, and to each other. And to do that, you cannot escape confronting the need for more density in cities. If we ignore these connected dots, we end up with Apple building a new Green headquarters in California powered by renewable energy but with 11,000 parking spaces.

Laura Bliss, also in grist, reinforces the need to concentrate on cutting vehicle miles travelled (VMT) and how that means that we will have to walk, bike or take public transit to work and play, and that in turn means building more dense residences near jobs, shops and shared transportation options. Shared transportation, or shared mobility, can include shared cars or small, sometimes automatic driven shuttle services providing transport for that last mile between home and job or public transportation or recreational and cultural facilities. It does not mean relying on Uber and similar services for a selected population.

Recently, David Roberts in vox has published a series of posts covering a conversation on urbanism he had with Brent Toderian, former Chief Planner for Vancouver. The first post is titled, “Making cities more dense always sparks resistance. Here’s how to overcome it.”

Vancouver has learned that density can include greater height in existing urban areas or multi-family units in formerly single-family areas or units along back lanes and alleys. Importantly it can mean extending public transit to new areas. Or all of the above.

Laneway house in Vancouver

Toderian argues that change in land use is often troubling and there will always be some who oppose change, the Not in My Back Yard (NIMBY) argument, just like there will always be developers who want to get rid of government regulation and build as much as they can, the build-baby-build cadre. See Interview with Oisín Coghlan in the current issue of www.irishenvironment.com

Both arguments can be countered by density that has a very high design quality, what Toderian calls QIMBY, “quality in my back yard,” with a diversity of housing types. Such development must, at the beginning, be multimodal with emphasis on walking, biking, and transit. It cannot be centered on use of cars. And the dense development must include amenities that make living in such neighborhoods enjoyable and even exciting. Amenities include parks and green spaces, public and people spaces, heritage preservation and community and cultural facilities, and places for teenagers to hang out.

To support many of the amenities, Toderian has used “density bonusing” whereby regulations set a base density for areas and a developer can increase to a higher density in exchange for building amenities that the community wants and needs, not basic services.

And when you have done all you can to accommodate as many as possible, Toderian argues that you just have to stand up to the anger of the few.

car free Oslo

Or perhaps adjust your plans. In Oslo, Norway, the car-limiting strategy was first to ban cars downtown, where about 88% of people did not own a car. But the automobile lobby fought vehemently against the ban. So Oslo has decided to limit vehicle movement through the city center by removing all parking spots and converting these spaces into installations and public spaces, for playgrounds, cultural events, benches, bike parking , a beer garden, and an e-bench with wi-fi and charging capabilities. Then the city will close some streets to vehicle traffic and build 40 miles of bike lanes. If these efforts fail to slash carbon emissions, then the city will go back to the original plan for an all-out car ban.

So regardless of how high the buildings get, don’t forget about those pesky GHG-vehicles on street level.

Sources

Henry Grabar, “If cities really want to fight climate change, they have to fight cars,” grist (16 June 2017). grist.org/article/if-cities-really-want-to-fight-climate-change-they-have-to-fight-cars/

Laura Bliss, “5 ways cities can fight climate change – with or without the Paris deal,” grist (1 June 2017).

grist.org/article/5-ways-cities-can-fight-climate-change-with-or-without-the-paris-deal/

David Roberts, “Lessons on urbanism from a Vancouver veteran: A conversation with city-maker Brent Toderian,” vox (20 June 2017).

www.vox.com/2017/6/20/15828464/urbanism-brent-toderian

Here are the conversations between Roberts and Toderian:

David Roberts, “Making cities more dense always sparks resistance. Here’s how to overcome it,” vox (20 June 2017). www.vox.com/2017/6/20/15815490/toderian-nimbys

David Roberts, “Young families typically leave cities for the suburbs. Here’s how to keep them downtown,” vox (21 June 2017).

www.vox.com/2017/6/21/15815524/toderian-families-cities

David Roberts, “Dense urbanism is great for downtowns. But what about suburbs?”, vox (23 June 2017).

www.vox.com/2017/6/23/15815510/toderian-suburbs

Justin Comiskey, “Dublin’s development plan short on density,” The Irish Times (17 Nov 2016).

www.irishtimes.com/business/commercial-property/dublin-s-development-plan-short-on-density-1.2867636

Henry Grabar, “Apple Says Its New Headquarters Could Be the Greenest Building in the World. Not With 11,000 Parking Spaces!”, Slate (12 April 2017). www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2017/04/12/apple_says_its_new_headquarters_is_the_greenest_building_in_the_world_not.html

Eillie Anzilotti, “If You Can’t Ban Cars Downtown, Just Take Away The Parking Spaces,” FastCompany (23 June 2017). www.fastcompany.com/40434409

No comments yet, add your own below