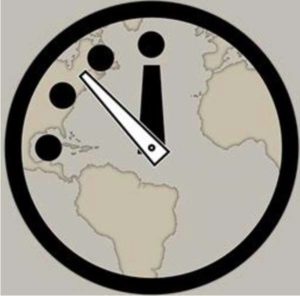

Tick Tock. Tick Tock.

What happens when the climate clock runs out?

The latest word from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in October 2018, was issued in its “Special Report” on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

The title is a mouth full but the report raised the level of anxiety on whether we can survive the current increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs), and subsequent rise in global temperature and extreme weather events. The initial takeaway from the IPCC report was that we have just 12 years to make rapid reductions in global carbon dioxide emissions in order to have any realisitc chance of averting catastrophic climate breakdown.

Some now argue that we really have only 14 months to save ourselves.

That short span derives from the fact that the aggressive cuts necessary to stabilize global warming below 2°C must begin now. “Scientific reality makes clear that the only plausible way to preserve a livable climate — and hence modern civilization — starts with aggressive national and global cuts in carbon pollution by 2030.”

The intriguing challenge here is whether we are at risk of losing a “livable climate” or “modern civilization.” There’s a big difference, with the former sometimes called a “catastrophic loss” and the latter an “existential threat.”

Arguing about whether climate breakdown will kill millions or billions, even all those alive, is, in one respect, an academic exercise, and a waste of time. Either way, it should be stopped.

But how bad the climate gets, or may get, does make a difference. What we do, and how much we spend, to stop the climate impacts may be affected by how many people are at risk. A geo-engineered solution may be uncertain and risky and costly, and not worth the risk unless it might save billions who otherwise would be lost.

What we do, and how much we spend, may also depend on who is at risk. Often left unsaid in climate breakdown discussions is the issue of wealth and economic inequalities.

Not surprising, rich people tend to take care of themselves and allow poor people to fend for themselves, knowing full well they cannot fend for themselves. There is no reason why such a course of action will not apply when it comes to climate breakdown.

For instance, on a small scale there are instances where rising sea levels can make an established, middle-class neighborhood, like beach-front property in Miamai, no longer sustainable. The middle-class people then move to less developed areas that are higher in elevation and subject to fewer risks, but still near their precious beaches. They then gentrify the climate-safe neighborhood. Such transitions already have been identified in Miami, Florida, including in Little Haiti, a historically lower-income Haitian neighborhood about a mile back from the beach but on higher ground. In Los Angeles, it is people moving to areas with reduced risks from fires that is contributing to higher real estate prices.” See “Climate Gentrification.”

On a larger scale floodwaters swamped more than a million acres of forest and farmland in the lower Mississippi Delta six months ago, and it is still above flood stage. US Fish and Wildlife Service staff refer to it as of “biblical proportion” and “Nothing like this has ever been seen.” Farming is the linchpin of the local economy and no farming has taken place since the flood. Some farmers will survive this year from crop insurance; some will not. All the businesses dependent on farming are on edge and many are concerned that the entire local economy will not survive. As the floodwaters have not yet receded, the full extent of the damage is unknown.

It does not take much imagination to see these various conditions reoccurring frequently, and affecting wider areas, as climate impacts intensify.

Poor, vulnerable people may be wiped out or extinguished by climate breakdown while rich, well-defended people will likely buy their way to a safe haven.

But if the impacts from climate breakdown spread wide and deep through an economy, then those with more at stake in the economy may have their lives disrupted, perhaps even destroyed.

And while the poor may be left undefended in one space, they will migrate to other spaces and countries looking for their own safe havens. These environmental or climate refugees will potentially disrupt entire government structures and economies, thereby affecting even the rich.

Until we figure out how to protect vulnerable members of our communities, and vulnerable communities among our nations, from the ravages of climate breakdown, noting is settled, no one can rest.

Sources:

IPCC, Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 ºC

www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

Kelsey Piper, “Is climate change an “existential threat” — or just a catastrophic one?” Vox (28 June 2019). bit.ly/2IJTVUC

Joe Romm, “We don’t have 12 years to save the climate. We have 14 months: The deadline for protecting our children from a ruined climate is close at hand,” Think Progress (26 July 2019). bit.ly/2GDCLIl

“Climate Gentrification” in iePEDIA section of irish environment magazine at bit.ly/2ymENIa

Patricia Cohen, “Where Floods of ‘Biblical Proportion’ Drowned Towns and Farms,” The New York Times (30 July 2019). https://nyti.ms/2YxrNxZ

No comments yet, add your own below