In the realm of climate action, National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) serve as guiding lights on the path toward the EU’s ambitious goal of achieving climate-neutrality by 2050. These blueprints hold the power to reshape our energy landscape and steer Member States toward a greener future. But as we delve into the significance of NECPs, it becomes apparent that a critical factor stands between their potential success and mere tokenism: meaningful citizen engagement, write Juliette Robert and Ruby Silk.

NECPs: The Mechanics

National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) are the cornerstone of the Energy Union. Introduced by the Governance Regulation back in 2018, they should keep our governments on track to meet the EU-wide target to become climate-neutral by 2050. The first round of plans was adopted 2019, outlining each Member State’s policy objectives, measures and targets in each of the five dimensions of the Energy Union, namely: decarbonisation, energy efficiency, energy security, the internal energy market, and research innovation and competitiveness. The plans cover a ten-year period and must be updated every five. Member States must also submit progress reports every two years, from 2023 onward.

Adopting a plan or updating it is a two-year long iterative process between each Member State and the Commission. Each country must first submit a draft to the Commission which then assesses it and can make recommendations. One year after submitting its draft, each government must submit the final version of their plan, taking the Commission’s recommendations into account.

2023 is an important year for the NECP process, as Member States must submit the draft update of their 2019 plan as well as their first biennial progress reports. However, eight months into the year civil society observers report that this process is woefully lacking in transparency and in public participation.

How must the public be included in developing the updated plans?

The draft of the updated NECP must be established in compliance with the public participation requirements enshrined in the Aarhus Convention. This international agreement guarantees minimum rights for members of the public to be involved in the preparation of plans and programmes relating to the environment. Parties to the Convention, including both the EU and all its Member States, must put in place a robust regulatory framework allowing the public to participate in a timely, inclusive, fair, effective and meaningful way.

The EU tried to implement those requirements in the Governance Regulation but succeeded only in a sloppy manner: Article 10 of the Governance Regulation provides for a mandatory public consultation in the preparation of the plan, but does not put in place a proper and robust legal framework to implement all the requirements of the Aarhus Regulation, and is therefore non-compliant.

Another way of involving the public is through the establishment of permanent multi-level energy and climate stakeholder dialogues (MECDs), required by article 11 of the Governance Regulation. Through these dialogues, representatives from civil society, business, academia, regional authorities, and other groups, can discuss the drafting of the NECP updates, however this is not an obligation.

Trying to bridge the gaps of the current text, the Commission issued a Guidance Notice in December 2022, laying out additional requirements in light of the Aarhus Convention to the Governance Regulation article 10 and 11. This Guidance Notice is however not binding for Member States, which can freely choose to disregard these additional recommendations.

How have these requirements been met by Member States?

For this round of NECPs updates, governments should have submitted their draft plans by 30 June 2023. However, in April 2023, a study conducted by Climate Action Network Europe and WWF revealed that most governments had not started any kind of public participation process in due time in order to comply with the Governance Regulation requirements. Evidence has also shown that article 11 (establishing MECDs) has not been well implemented across the EU and that multilevel dialogues are missing in most Member States. Environmental NGOs called upon the European Commission in a subsequent letter to exercise its role as guardian of EU law and to recall to governments their obligations relating to environmental democracy.

Two months after the submission deadline of the draft updates, the dedicated European Commission website shows that only 15 of the 27 Member States have submitted a draft plan. From a quick review of their content, it seems that national governments have heeded the call from the Commission and civil society for to take better regard of the outcome of the public participation processes. Indeed, most of them have reported on some sort of public participation process, even if the said process was unsatisfactory, as revealed by the study mentioned. Environmental NGOs are now counting on the European Commission to evaluate the quality of these processes according to the Aarhus standards in its assessments of the drafts, which should be published by the end of the year.

Meaningful participation in the environmental decision-making processes also entails that the participating public is fully informed. In that regard, transparency is key, regarding both the updating process and the progress reports, which should have been submitted by March 15 of this year. Having access to these reports is essential to guide participation in the updating of the NECPs. Many progress reports have however still not been published in full, either by the Commission or by the Member States themselves.

What can be done going forward?

The fight for better public involvement in the elaboration of these updates is not over. Member States will have to conduct another – if not the first – round of public consultations once they modify their draft following the Commission’s assessment.

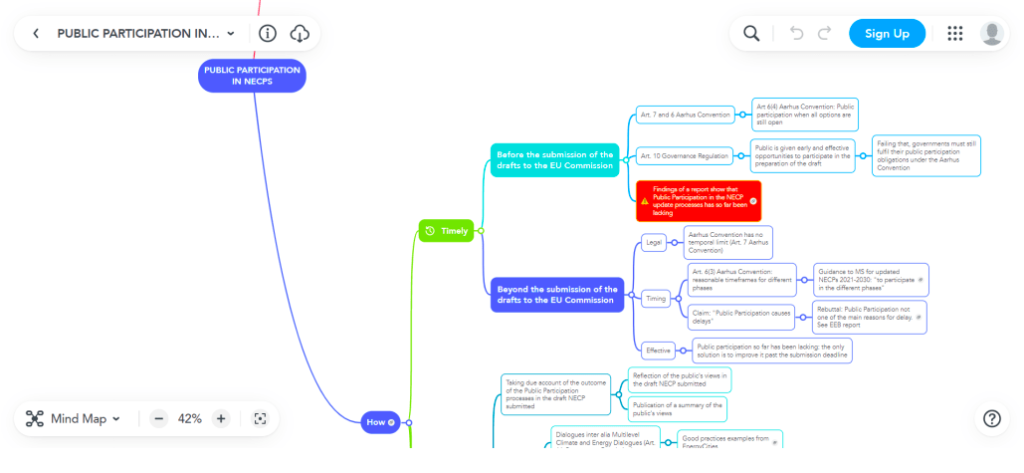

This mind map, developed by the EEB, can be used to guide Member States in this process and to help them understand the safeguards that must be put in place to ensure quality public participation. It can also be used to put forth arguments demanding that the public has a say in this ultimate stage of the updating process.With the requirements of article 10 (public consultations in the preparation of NECPs) being as unintelligible and incomplete as they are, this checklist will also be a useful tool to guide national authorities on how to conduct a proper public consultation.

(See published version for readable version of Mind Map).

As National Energy and Climate Plans are going to lay the foundations for future energy and climate action within each country, it is essential that people have a real opportunity to influence their content and that public participation processes are not reduced to mere ‘citizenwashing’ exercises.

Originally published by European Environmental Bureau, META (14 Sept 2023). bit.ly/3RBmIjr

Author:

No comments yet, add your own below