Background

To address the causes of climate change, we need to eliminate, or mitigate, as far as possible the continuing emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) — this is imperative — and at the same time we need to prepare for, or adapt to, the inevitable effects of climate change that will occur.

The European Union (EU) published a guideline for climate change adaptation in 2009, followed by a European Climate Adaptation Platform or Climate-ADAPT, to help member states to develop adaptation tools, strategies and options. The Irish government published a National Climate Change Adaptation Framework in December 2012.

The Irish Framework document was covered in an earlier Report (Feb 2013) in this magazine, “Ireland’s Climate Adaptation Strategy: The Emperor Has No Clothes On.” There we pointed out the failings of Ireland’s adaptation framework and noted “The report says almost nothing concrete about adapting … [and] fails to advance an understanding or commitment to what specifically has to be done to adapt.” As we further noted, “the report is particularly disappointing as there has been solid research and case studies on both models for and practical applications of adaptation,” including work done under the EPA Science, Technology, Research and Innovation for the Environment (STRIVE) research programme.

In a series of more recent reports, under the STRIVE research program, the Irish Climate Analysis and Research UnitS (ICARUS) at the Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, advances the data, analysis and applications for developing a concrete and viable adaptation policy and plan in the Republic of Ireland (RoI). We will look closely at one of the reports, Co-ordination, Communication and Adaptation for Climate Change in Ireland: An Integrated Approach (COCOADAPT), which serves as an abbreviated version of the work in the other reports. See Sources for this and the other, related reports from ICARUS.

Whether the Irish government, local authorities, and others take advantage of this work remains to be seen. As the COCOADAPT report notes, with some resignation, in regard to Irish adaptation plans generally, “An element of rebranding of existing policies is often evident in such exercises and mainstreaming of climate adaptation into national legislation is often quite limited.”

The COCOADAPT Report

Introduction

Certain characteristics of adaptation have become clear over the past several decades, and they are helpful for understanding what more is needed.

Uncertainty hangs like a ghost over any plans to adapt. We know that severe impacts from climate change are coming but not exactly when or precisely where or how. The report notes that nevertheless we can adopt “no-regrets strategies” in the face of this uncertainty. Many impacts from climate change are simply the intensification — more often, more extreme — of hazards we are familiar with already, such as floods, heat waves, droughts, and loss of biodiversity. So adapting to the extreme forms of these events need not be regretted.

Such thinking makes sense but it does carry a risk. Many levels of government are simply “rebranding” existing policies and plans, e.g., for flooding, as “climate change adaptation” but they do not always account for the increased intensification of such events.

With rebranding, the government, or its departments or agencies, often leave the existing administrative structures in place, with several agencies responsible for different aspects of the policy but no coordination between them. Yet a coordinated approach, across all relevant agencies or departments, is critical to forming a coherent climate change approach that can adapt to the worst effects.

The uncertainty demands flexibility to adjust to the climate change effects as they unfold. As the report notes:

Adaptation is increasingly seen as not a process with an end point, but rather an iterative feedback process to be constantly renewing itself as better knowledge concerning climate change scenarios and impacts become available. At 3.

Instead of focusing on predicting set impacts occurring over short terms, the report adopts a ”vulnerability” approach that focuses on flexibility with long-term planning to offset the uncertainty.

Water Resources

The report relies on various models and data sets to develop four future scenarios that account not only for climate change but also other factors that will affect water resources, including demand from population changes and reduction of leakages from water supply systems. The models are (A) Business as usual, where there is no population increase, no more demand, same supply, and no change in current leakages; (B) Reduced Water Demand, where other factors remain constant but there is reduced demand by 5% by 2020; (C) Reduced Leakages, where demand stays the same but leakage is reduced from current 43% to 25% by 2015; and, (D) Reduced Demand and Reduced Leakage.

The authors then apply these tools to two case studies: River Boyne, and River Glore. The work shows that climate change will increase the vulnerability of these, and other, water supplies but that reducing the leakage and demand can reduce the occurrence of water stresses. Yet the models also demonstrate that these levels of adaptation may not be sufficient to protect water supplies against climate change and more is required than accounted for in the scenarios, including alternative water supplies. In addition, any new investment in water infrastructure needs to take into account the possibilities and uncertainties associated with climate change.

Biodiversity

To assess the adaptation measures applicable for protecting biodiversity in Ireland, the report examined a series of datasets for 274 species and 20 habitats and modeled several scenarios: unlimited dispersal, where species can colonise all potential new areas; and fully limited, where species could not colonise potential new areas. The report then provides assessments for various species and how they may fare under climate changes. For example, moss liverwort and fern species are projected to have a contraction of their range, and species at higher latitude and altitude will suffer the largest range contractions as they have no where to go. The habitats that will be most vulnerable to climate change impacts include upland habitats, peatlands, and coastal habitats.

To assist species in migrating to avoid climate change impacts, the report recommends a maintenance and promotion of “connectivity” in the wider landscape, including more green infrastructure. See “Landscape Connectivity” in the iePEDIA section of the current issue of irish environment. It is suggested that agri-environment measures will be critical to providing connected space for species dispersal and migration.

Ultimately, not all species will be capable of migrating and conservation efforts may need to focus limited resources on these species, even through assisting migration. While there are measures currently being implemented to conserve species under threat, what the report, and its tools, provide are ways of assessing what species in the future will be most vulnerable under climate changes and what specific adaptation measures they require to survive.

Construction

An interesting dimension to the Maynooth report is the analysis of adaptation needs for two sectors of the economy, construction and tourism.

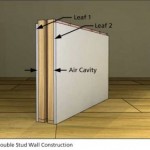

For the construction sector, which contributed 25% of GDP at its peak in 2006, the report focuses on the impacts from wind-driven rain, domestic wastewater treatment (septic tanks), and building regulations. Based on rain data and modeled climate change, the report indicates that wind and rain will increase with resulting surface wetting, wear on facades, roofs, windows and doors. Wetting will increase from 7% to 16%, and the western coastal zones will be most affected, but also with significant impacts in inland areas. Walls will be wetter for longer with stress on heating systems and increased mould. As a result the report recommends that in exposed areas there be restricted planning permissions, and double-leaf housing construction in more inland areas.

Ireland can expect significant problems associated with septic tanks as a result of increased precipitation and rising water tables, from climate change, as well as from lack of mains sewage and further housing developments. About 40% of the population lives in rural areas, with many having no access to mains sewage. Newer septic tanks have been subject to tighter regulations, and should present minimal threats. The same cannot be said about legacy septic tanks, which are only now being subjected to a limited inspection regime.

Ireland can expect significant problems associated with septic tanks as a result of increased precipitation and rising water tables, from climate change, as well as from lack of mains sewage and further housing developments. About 40% of the population lives in rural areas, with many having no access to mains sewage. Newer septic tanks have been subject to tighter regulations, and should present minimal threats. The same cannot be said about legacy septic tanks, which are only now being subjected to a limited inspection regime.

While the expectation was that rural areas would experience more problems with septic tanks, the data showed that the greater problems would be in areas where septic tank density was greater than 16 per square kilometer, namely urban areas.

The report recommends that all building regulations be required to account for reasonably foreseeable conditions, which of course will change as the climate changes. The report argues that “In a construction context, the cost of over-adaptation is minimal compared to the cost of under-adaptation.” At 26.

Tourism

Ireland’s natural environment has always been a major draw for tourists. The weather has not always helped, but the dry humor and warmth of the people on the island helps to offset the weather. It is expected that temperature will warm perhaps by 2.5°C in July by 2050, with temperature rises in most seasons. As a result, opportunities for the tourist trade, including a longer season, will expand. Current popular warm-weather resorts throughout Europe likely will become too hot for many.

Countering these advantages will be greater winter flooding in some areas and reduced precipitation in the summer in the south and east with resulting impacts on already-stressed water supplies. Water shortages are likely just when more tourists may be coming to visit.

The report recommends that areas that will be subject to limited water supplies need to take action now to upgrade water infrastructure and develop other sustainable practices. There are a whole range of options already available, including capture and use of grey water, rainwater harvesting, and carbon-neutral eco-tourist activities.

Economic Analyses of Climate Impacts

The COCOADAPT report also provides an economic assessment of certain climate impacts on sea level rise, coastal wetlands, and inland flooding to indicate generally the scope of the problem. This work follows on the seminal work by the Stern Report on global economic consequences of climate change. The costs were valued on basis of sea level rises (SLR) ranging from 1 metre to 6 metres.

Approximately 350 square km of land is exposed under a 1 metre SLR with potential economic costs relating to property insurance claims in the region of €1B. Impacts relating to wetlands under a 1 metre SLR are modelled at 14-49% of potential losses dependant on wetland type with economic cost estimated at approximately €24M per year. Modelling relating to inland flooding carried out on four Irish river catchments under a 2 metre river network elevation buffer found over 1,800 exposed properties with potential insurance claims in the region of €46M. Of course, with higher SLR, the costs will escalate significantly.

Approximately 350 square km of land is exposed under a 1 metre SLR with potential economic costs relating to property insurance claims in the region of €1B. Impacts relating to wetlands under a 1 metre SLR are modelled at 14-49% of potential losses dependant on wetland type with economic cost estimated at approximately €24M per year. Modelling relating to inland flooding carried out on four Irish river catchments under a 2 metre river network elevation buffer found over 1,800 exposed properties with potential insurance claims in the region of €46M. Of course, with higher SLR, the costs will escalate significantly.

The report indicates that such outcomes highlight the importance of the Integrated Coastal Zone Managements and Catchment Flood Risk Assessment and Management Studies that are ongoing or planned.

Governance

All the scientific and economic and environmental tools available for adapting to climate change will be wasted if there is no comparable political will and action on the part of government agencies to use the tools and implement concrete adaptation.

The report looked at the existing sub-national, and national, policies and plans to assess what is currently possible. The authors evaluated the exposures, impacts and vulnerabilities each county would be subject to, and what barriers and opportunities and high-level government plans were available to the counties. Assessing risks from landslides, lower water supply, coastal erosion and sea level rise, the report found few local governments prepared to adapt, a lack of standardized approach to climate change, and little vertical integration between the national and local governments.

The local governments identified the three most common problems as shortage of resources (staff and money), competing priorities (development and agriculture and economic agendas), and integration (both horizontal and vertical). There was some proactive leadership found in Dublin City Council, notably the Greater Dublin Sustainable Drainage Study, with some smaller councils adopting Dublin’s plans and actions and promoting public awareness. Flooding protection and public transport seem to be the two areas that receive the most attention by local councils.

County Mayo Case Study

A significant contribution of the COCOADAPT study is its concrete, specific application of the science behind global climate change to the challenges of adaptation for Ireland. This is most evident in the case study of County Mayo where the report takes the data, modeling and concrete analyses applied throughout the study and draws it down to the level of conditions found and to be found in a single county.

The report projects that County Mayo, like the rest of Ireland, will warm by 3-4°C over this century, resulting in July temperatures at about 18°C and mean January temperatures comparable to a current average April. Precipitation modeling is less certain but it is likely summers will be significantly drier, with more extreme rain events and more frequent drought periods. Winters will be wetter, by as much as 25%, and the sea along the Mayo coast will rise by 0.5 – 1 meter this century.

A reduction in demand and fixing leaks for water resources in Mayo will likely avoid major problems in the supply of water. On the other hand, Mayo is rich in nature conservation sites and in biodiversity and full implementation of the Habitats Directive, taking into account climate change projections, will be necessary to protect these resources. These natural resources, along with the longest coastline in Ireland, and the important pilgrimage sites at Knock and Croagh Patrick, open up more opportunities for Mayo in eco-tourism as long as the resources and sites are protected against the impacts from climate change.

Mayo’s low and widely dispersed population, with 71% living in rural areas, avoids many of the problems associated with dense septic tank areas around urban areas in other parts of the island. Yet increased precipitation will create risks to pollution from septic tanks because the water table in many areas of Mayo is close to the surface. As a result there should be strict limits on septic tank construction in areas of impermeable soils and density of septic tanks, and enhanced groundwater monitoring to check on rising water tables.

Sitting on the western fringe of Ireland, Mayo is subject to wind-driven rain, which is expected to rise by 14%, and, as we have seen above, building regulations will need to account for these climate changes through tighter planning, limiting sites suitable for construction, and requiring more resilient building materials, such a double-leaf construction.

Like other areas of Ireland, Mayo will be subject to high exposure from landslides, coastal erosion and sea level rise, and yet few actions have been taken by local authorities for climate change adaptation, and little mainstreaming of these issues has occurred

Conclusion

County Mayo is lucky to have been provided a blueprint for what it needs to do to prepare for climate adaptation. The problem is that as with all blueprints, someone now has to go ahead and build the structure.

A serious question arises as to whether local governments have the technical expertise, staffing, and financial resources to develop and carry out the kind of concrete adaptation strategy and plans as we see in the COCOADAPT study, especially in the case study for County Mayo. But when we look to the national government for proactive leadership, it seems sadly lacking.

The national government does not seem to have gotten beyond its fragmented approach to climate change. Its pronouncements on adaptation seem dominated by deferring action to other layers of government, with little in the way of incentives or standards for adaptation policies. In contrast we see other governmental agencies taking proactive, concrete actions to deal with climate change adaptation. A recent example is that the New York Public Service Commission (NYPSC), which has approved new rates for electricity, steam and gas in New York City, has required Consolidated Edison (ConEd), New York City’s largest electric utility, to study how climate change will affect its infrastructure and how to adjust its operations to mitigate those effects.

Where there is a will, and some power, there is a way.

It is just another wink and a nod for the national government to adopt a national climate change adaptation plan that simply turns over the responsibility for adaptation to local authorities that it knows are not equipped to do the job. A more productive approach would be for the national government to pay for the development of specific adaptation strategies for each local authority, and to fund the implementation of the strategies, possibly with revenue from a full carbon tax.

Sources

Co-ordination, Communication and Adaptation for Climate Change in Ireland: An Integrated Approach (COCOADAPT), EPA STRIVE

Programme 2007-2013 (Sept 2013). Prepared for the Irish Environmental Protection Agency by The Irish Climate Analysis and Research UnitS (ICARUS), Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Authors: John Sweeney, David Bourke, John Coll, Stephen Flood, Michael Gormally, Julia Hall, Jackie McGloughlin, Conor Murphy, Nichola Salmon, Micheline Sheehy Skeffington and David Smyth. www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/research/climate/climatechangeresearchreportnumber30.html#.Uve_mfYebp8

Related studies by ICARUS/Maynooth as part of the Irish EPA STRIVE Programme 2007-2013:

HydroDetect: The Identification and Assessment of Climate Change Indicators for an Irish Reference Network of River Flow Station (Sept. 2013). Authors: Conor Murphy, Shaun Harrigan, Julia Hall and Robert L.Wilby www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/research/climate/CCRP_27.pdf

Winners and Losers: Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity in Ireland (Sept 2013). Authors: John Coll, David Bourke, Michael Gormally, Micheline Sheehy Skeffington and John Sweeney www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/research/climate/CCRP_27.pdf

Current and future vulnerabilities to climate change in Ireland (Sept 2013). Authors: John Coll and John Sweeney www.epa.ie/pubs/reports/research/climate/CCRP_29.pdf

“Ireland’s Climate Adaptation Strategy: The Emperor Has No Clothes On,” in the Reports section of irish environment (February 2013) www.irishenvironment.com/reports/irelands-climate-adaptation-strategy-the-emperor-has-no-clothes-on/

“Landscape Connectivity,” iePEDIA section of the current issue of irish environment (March 2014).

“New York Utilities Now Required To Prep For Sea Level Rise, Extreme Weather, Climate Change,” Huffington Post Green, from Bobby Magill, Climate Central www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/25/new-york-utilities_n_4855888.html?utm_hp_ref=green

No comments yet, add your own below