Mercury rising does not refer to the Bruce Willis film, or to the mercury in thermometers that is rising because of climate change. Rather it is about the toxic mercury rising in the environment creating health risks, as well as adverse effects on wildlife.

In a recent report from the European Environment Agency (EEA), the presence, source and risks of mercury, as well as what is being done about mercury contamination, are assessed.

Mercury has been around for thousands of years as it occurs naturally in the Earth’s crust. But it has been the formation and use of mercury in industrial processes, as well as in gold mining and burning of fossil fuels, that has created the risks to health and the environment. Over the past 500 years between one and three tons of mercury entered the environment.

Typically mercury is emitted into the atmosphere where it can travel long distances and then is deposited in lakes, rivers, and oceans. At times the mercury has been dumped directly into a water body along with production waste, as happened in Minamata, Japan. It can circulate in the environment for up to 3,000 years.

While less dangerous in the air and in soil, once in water the mercury is converted to methylmercury, a most toxic substance. In the water environment the toxic mercury is absorbed by fish and animals and then it moves up the food chain, reaching humans and animals with devastating effects.

The threats to wildlife remain. Over the past several decades there has been a risk for bald eagles in the US from eating fish contaminated with mercury. In addition, recent studies have shown that mercury contamination has affected about 46,000 out of a total of 111,000 surface water bodies in the EU, exceeding the safe concentration for fish-eating birds and mammals. With climate change, there will be increased risks from mercury spreading as a result of more, and more intense, flooding and precipitation.

Most vulnerable are foetus, newborn babies and children as we learned in Minamata, the most infamous site for methylmercury poisoning. In Minamata, a chemical company dumped wastewater contaminated with mercury into the sea at Minamata. The sea was the major source of subsidence for many in the community as well as their main source of income. The mercury converted to methlymercury and the fish ingested it. Fish began to disappear from the sea, and then started to wash ashore, dead. The wild cats of the area feasted on this trove of dead fish, and soon they started to act crazy, running around and bashing themselves against walls, and finally jumping into the sea to drown. Then the disease, or whatever it was, jumped species and people who ate the fish started to go crazy: mumbling to themselves, incoherently, falling down in convulsions, shouting and crying uncontrollably. Pregnant women also ate the mercury-contaminated fish but were unaffected by the mercury because it passed directly to the placenta and infected the foetus. Soon a congenital form of the mercury poisoning showed itself in newborns who were unable to speak or hold their heads up or control much of their body.

As many of the afflicted with what became known as Minamata Disease were from the same family (they shared contaminated fish), the community believed the disease was contagious. The victims of the disease were ostracized. They had to leave their money on the floor of shops so no one had to come in direct contact.

The community’s treatment was exacerbated by the chemical company’s denial of any responsibility (knowing full well that it was the source of the contamination), and by the government’s support of the chemical company instead of the victims.

The victims never gave up and after decades of organizing, protesting and, finally, litigation, the chemical company was found responsible and had to apologize and compensate the victims. The government was also found to be culpable.

But the suffering of the victims who survived continues to this day.

What’s Being Done About Mercury

Over the past several decades efforts have been made to reduce the impacts from mercury on the environment and health. In 1998, the Aarhus Protocol on Heavy Metals (UNICEF) was adopted, and came into force in 2001. Its main function was to reduce mercury use in products and in emissions. In response to the Protocol, the EU adopted a number of policies on mercury in emissions. Then the a UN -commissioned study found that mercury still presented significant risks and that further protective measures were necessary.

In 2013 the international Minamata Convention was adopted, and ratified in 2018 by over 100 countries. It focuses on prohibiting mercury mining, phasing out use of mercury in industrial processes, requiring safe management of mercury waste, identifying sites contaminated with mercury, and promoting the monitoring and knowledge about mercury. Critically, the Convention is binding on those nations that ratify it and is enforceable through the International Court of Justice.

The EU proceeded to strengthen protections beyond those provide in the Convention. All new uses of mercury were banned, deadlines were set for ceasing the use of mercury in industrial processes, and extensive waste management regulations were approved.

Within the EU, Sweden has been particularly watchful, especially since observing the high levels of mercury in birds and fish in the 1950and 1960s. Sweden has taken a series of initiatives to address mercury in its environment, including a national strategy to reduce emissions and banning mercury use in dentistry and other services. Nevertheless, more than 23,000 water bodies in Sweden are still impacted by mercury pollution, and health advisories covering the eating of fish have been issued. Despite the Swedish efforts, it has been estimated that most of the mercury impacting Sweden originated outside Europe and only 1% is generated in Sweden.

Conclusion

In light of the proactive measures adopted by the EU, and yet the continuing adverse impacts from mercury in the environment, what else can the EU do?

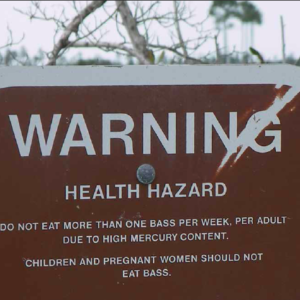

A major takeaway is that the primary pathway for exposure to dangerous levels of mercury is through diets, namely eating a lot of fish contaminated with mercury. So fish-eaters remain at risk from mercury. At the same time, fish provide critical nutrients to many poor communities, and those in more developed countries are being encouraged to eat fish instead of meat, the production of which generates substantially higher levels of GHG emissions. One important initiative is to advise people about the risks presented by eating certain fish in certain quantities. These “fish advisories” differ from place to place but typically they cover predatory fish, including tuna, swordfish, shark and marlin. In Ireland, for instance, pregnant or trying-to-be pregnant women, breast-feeding women, and young children are advised not to eat swordfish, shark or marlin at all, and to limit consumption of tuna to 1 steak or 2 cans a week.

In the US, fish advisories are issued generally by state or local health agencies. Unfortunately, while the EU continues to monitor and regulate mercury in the environment, the Trump administration continues to undermine environmental protections against mercury poisoning in the US. The Trump EPA is in the process of deregulating controls over mercury emissions.

Both mercury and CO2 remain in the environment for thousands of years and they travel long distances to affect places far away. As a result, what is emitted now will be with our childrens’ childrens’ children. As we learned from Sweden, what we do alone will never be enough.

Sources:

EEA, Mercury in Europe’s environment: A priority for European and global action (19 Sept 2018). bit.ly/2J229HH

Fiona Harvey, “Eat less meat to avoid dangerous global warming, scientists say,” The Guardian (21 Mar 2016). bit.ly/2biC6KU

University of Montreal. “Mercury rising: Are the fish we eat toxic?” Science Daily, 3 May 2018. bit.ly/2J4Ffzo

Nu3, Food Carbon Footprint Index 2018 bit.ly/2pZFJhD

No comments yet, add your own below