Background

Last month we looked at several reports on marine litter/waste that addressed what’s visible, and toxic, in the marine environment. This month we look at five reports, from the International Program on the State of the Ocean (IPSO), in cooperation with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), on what’s not so visible but critically dangerous for the health of the ocean: climate warming, acidification, and deoxygenation.

The first step necessary to dealing with these dangers is to recognize what is at risk. Many depend on the ocean for subsistence, recreational, or commercial fishing, and they appreciate the value of the ocean as a resource. A few sail or cruise the ocean for adventure. Many experience the ocean only through occasional or periodic recreational use, primarily swimming and surfing. Often lost in these encounters is the symbiotic relationship between our life on land and what happens, or doesn’t, in the ocean, and we know much less about the ocean environment than we know about the land environment.

All the oceans are connected to each other and form one ocean, so we can speak about the ocean or oceans. Some things about the ocean are familiar: oceans cover 70% of the earth’s surface, they contain 97% of the earth’s water supply, and life on earth originated there. The oceans absorb solar radiation and carbon doxide (CO2), affecting weather and temperature on land. As we will see in these IPSO reports, this particular function is critical and changing, for the worse.

Lately, efforts are being made to calculate the economic value of the ocean and we have learned that the ocean and coastal ecosytems provide as much as two-thirds of the planet’s natural capital.

Ocean fisheries provide 80 billion USD, 35 million jobs and the livelihood and food for 300 million people in coastal communities.

Coastal ecosystems provide food, fibre, firewood, recreation, habitat and shoreline protection, and water filtration, as well as carbon cycle benefits.

The recently published Summary of the 5th Report by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has indicated the serious assaults by human activities on various parts of our environment, including oceans, and the consequences of these assaults over short and long periods of time. With regard to the ocean, the IPCC has warned that it is absorbing much of the global warming and carbon doxide (CO2) and it cannot continue to do so, with serious impacts on life on land. The IPSO argues that in fact the IPCC has underestimated the impacts, and consequences, which are far graver than previous estimates.

Climate Change and the Ocean: a deadly trio of impacts

The worse effects of rapid climate change have been softened somewhat because the ocean has been absorbing excess CO2 from the atmosphere, in effect saving ourselves from ourselves. No longer. The ocean is now paying a deadly price, and so will we. The ocean is warming, it is getting dangerously acidic and it is losing its oxygen; it also continues to suffer from pollution, eutrophication, and overfishing.

To get a sense of the scale of the changes being wrought, the current acidification is unparalleled in at least the last 300 million years, and the current rate of carbon release, at 30 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 per year, is at least 10 times that which preceded the last major species extinction. Those are impressive, and scary, numbers.

With the rise in ocean warming, the results are well documented and include: disappearance of Arctic summer sea ice, more sea level rise (warm water expands), greater loss of oxygen, increased storm intensity and increased venting of methane from the Arctic seabed. These results in turn are leading to a variety of consequences. For example, some species, which cannot survive in warmer water, will have to undertake a poleward-shift in migration of between 30-130 km, and 3.5 meters deeper. For some coastal species of fish, they will run out of coastline to migrate along and be blocked by further migration. This redistribution of commercial fisheries will diminish the fisheries in tropics, but possibly increase fisheries in higher latitudes – the poor get poorer, the rich get richer.

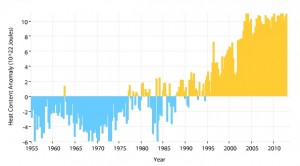

This graph shows differences from the long-term average global ocean heat content (1955-2006) in the top 700 meters of the ocean. NOAA

The rise in CO2 is causing a reduction in ocean pH which leads to an increase in acidity, which in turn leads to a loss of calcium carbonate, a substance that is critical for forming coral reefs and sustaining crustaceans, molluscs and other planktonic species. The combined warming and acidification likely will lead to further decline of tropical coral reefs by 2050. While warming will drive species north toward colder waters, acidification, which happens faster in colder water, will drive migration southward.

The last of the trio, deoxygenation, reflects a broad level of declining oxygen in tropical oceans and areas of the North Pacific, and dramatic increase in loss of oxygen in coastal waters, especially near large population centers and large water sheds. The former results from global warming and the latter from increased eutrophication from runoff of agricultural fertilizers and sewage pollution.

The unholy trio will wreck havoc on the marine ecosystems, aggravating the ongoing destruction of fish stocks by overfishing.

Fisheries: aquacalypse or not

With the global population at about 7 billion, and heading toward 9 billion by 2050, seafood as a staple for poorer communities will become even more critical. Ocean fisheries that supply much of that staple have been under threat for decades, from overfishing and other stresses, leading some to predict an aquacalypse. Recent reports suggest that the threat may be lessening, in part from better managed fisheries. The IPSO report is clear that the optimism is unfounded because the positive findings are limited to the better-managed fisheries in the developed world, where there has been some positive impact from best practices, while the conditions in developing countries are elusive, from lack of data, and are still deteriorating because of loose or non-existent regulation and management. More than 50% of countries were found to be failing to comply with existing, and weak, regulations.

Since only 16% of the annual world fish catch is from better-managed fisheries in North America and Europe, the remaining 84% remains at high risk. The risk is reflected in the studies showing that 70% of world fish populations are unsustainably overexploited. Also fishers have to work harder to get less, as reflected in studies showing that total engine power and number of fishing days steadily increased from 1970s. The overfishing is leading to extinction of 55% of marine species, loss of biodiversity in the oceans, and an estimated 27 million tines of by-catch (including dolphins, sea-birds, and turtles) discarded each year.

These pressures come from fishing intensity with new technology and the global commerialisation of fishery products, and they are aggravated by changing environmental conditions associated with climate change.

The IPSO report points out that some of the problems are correctable, with enhanced regulation and enforcement (see discussion below). For example, environmentally damaging fishing gear, like bottom trawls, dynamite fishing, high bycatch and discards and ghost fishing (lost gear trapping and killing fish) can be minimized. The report provides detailed analyses of methods for assessing fisheries, and suggests ways of addressing the risks. Some of the ways forward are through eliminating subsidies that support harmful practices, banning harmful fishing gear, combating illegal and unreported fishing (estimated at 35% of global catches), and enhancing science-based assessments. An important recommendation is the call to work with indigenous communities and other local, small-scale fisheries to counter the adverse effects of globalization.

Climate Change and Coral Reefs

A coral reef is a particularly vulnerable marine ecosystem that is sensitive to all sorts of environmental changes, whether on a global or local level. Coral reefs also serve as a supply of food for a substantial number of the world’s poorest people.

In the past the major threats to coral reefs were from industrial pollution, sewage and land runoff, and direct disturbances such as dredging, as well as from overfishing. Most of these threats were the result of proximity to populated areas. The threats from climate change, including warming and acidification, are reaching even isolated coral reefs.

A critical contribution of the analysis of the growing risks to coral reefs is the focus on, and ellucidation of, the interactive effects of ocean warming and acidification, along with local effects from pollution, sedimentation and overfishing on coral reefs. And these global and local impacts have differential effects in different places at different times. For instance, coral reefs in wealthy areas are affected by coastal development whereas coral reefs near poorer communities are affected more by chemical and sewage discharges.

Just as we are experiencing more frequent and more intense weather storms on land, we are also finding more and more intense thermal events affecting coral reef bleaching. The reduction in calcification rates results in less dense skeletons in corals which in turn makes them more vulnerable to diseases and damage from tropical storms. It is a vicious circle.

The prognosis is not encouraging. The current climate change target under global negotiations is a 2 degree C rise in global temperature, caused by 450 ppm CO2e. At that level, coral reef organisms will exhibit very low calcification rates and will cease to grow; at slightly higher temperatures, the reefs will start to dissolve. In other words, current targets for CO2 emissions serve as a death sentence for coral reefs.

Legacy contaminants and emerging chemicals

Analytical chemistry has played a key role in identifying, monitoring, and evaluating the threats to the oceans from chemicals. Historically, oceans have been subjected to threats from what are called “legacy” contaminants, which include persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) chemicals such as cadmiuim, lindane, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). These legacy chemicals have been monitored since the 1970s and regulated for a number of years. These threats are now compounded by “emerging chemicals,” which are those that have been detected in the environment, are not part of a regulatory monitoring programme, and whose fate and effects are largely unknown. Examples of these emerging chemicals are brominated flame retardants, perfluorinated compounds, personal care products, and medicinal pharmaceuticals.

These contaminants and chemicals, along with some natural chemicals, such as algal biotoxins, have posed a threat to marine ecosystems and human health by way of the food chain. The threats remain active and alive and in need of corrective action.

The IPSO report on the issue delves into the methodologies of chemical analysis and monitoring and provides examples of PAHs as a legacy contaminant and decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) as an emerging chemical. The report recommends several methodologies for better assessing the chemicals and suggests that it makes sense to target key groups of chemicals of concern rather than trying to monitor large groups of emerging contaminants with analytical chemistry.

Ocean in Peril: reform in managing ocean assets

The oceans are also called the “high seas,” and generally include all parts of the oceans that extend beyond a country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or other areas under the jurisdiction of one or more countries. The challenges are obvious: how does anyone patrol the high seas, and monitor and enforce any regulations that do exist? Just as the threats to the oceans are largely invisible, the oceans are vast and out of the sight of most people and governments.

There are some existing agreements that attempt to create sustainable fisheries and maintain marine biodiversity in the high seas, including a series of regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) set up under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The RFMOs are independent of each other and their rules and decisions apply only to the countries that are members of the RFMO; some countries do not belong to any RFMO. Despite some RFMOs that have been successful, two thirds of all fish stocks under RFMO management, for which the status is known, are depleted or being overfished. In addition, there is wide-spread illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing on the high seas. The legal and policy mechanisms to protect resources in the high seas are limited and, in many instances, not particularly effective.

The shortcomings have been well documented. The RFMOs are comprised of States with a direct economic interest in a fishery, and the members of the RFMOs generally come from the fishing industries. In effect, the foxes are guarding the hens. There is very little oversight, monitoring or enforcement for what rules do apply. There are few voices on the RFMOs that represent conservation or environmental or even science concerns, and no representation of any global perspective in spite of the globalized nature of modern high-seas fishing fleets and trading practices .

While there is general agreement within many governments that fisheries management needs to become ecosytem-based and precautionary, getting there is largely unmapped. The IPSO report provides a detailed road map for what can be done to correct the inadequacies of the present regulatory system. Three routes are provided: (1) a soft approach with UN resolutions calling for state of the practice, science-based management; (2) reform of the RFMOs (better best practice guidelines, with enhanced inspection and monitoring of fleets and enforcement of rules); and/or (3) fundamental, structural reform in the nature of a new agreement under the UNCLOS.

The IPSO report clearly favors the third approach, which would include the first two. The new agreement would provide the reforms outlined in the first two options, and in addition, among other recommendations: require environmental impact and strategic environmental assessments for potentially destructive or extractive activities; require that those utilizing resources or engaging in activities that affect the high seas beyond national jurisdiction to prove their activities comply with law and will not cause significant adverse impacts, alone or in conjunction with other activities (burden of proof); and, establish a compliance commission and dedicated enforcement agency with powers to initiate judicial proceedings.

These three specific recommendations are well considered, and tough, and would go far to correct some of the shortcomings of the current regime. They possibly could even be implemented by the RFMOs, without full re-negotiation of the UNCLOS, but the vested interests of the parties that control the RFMOs would likely assure they do not come to pass. While the negotiations for a new UNCLOS would be prolonged and complicated, at least the wider conservation, environmental and science communities would have their voices heard and have an opportunity to impact the outcome. That would likely not happen with reforms of just the RFMOs.

Conclusion

What’s the bottom line? The authors of the report say it best in the Executive Summary: “We have been taking the ocean for granted. It has been shielding us from the worst effects of accelerating climate change by absorbing excess CO2 from the atmosphere, and this has created a ‘deadly trio’ of impacts – acidification, warming and deoxygenation – which are combining to dramatic effect on the flora and fauna of the ocean, and exacerbating the effects of other factors, such as pollution, eutrophication and overfishing.”

A major contribution of the IPSO reports is the insistence on dealing with the interaction between the various stressors from climate change — warming, acidification, deoxygenation — and local stressors, mainly from pollution, eutrophication, and overfishing.

The IPSO offers a complex analysis that is well worth working through to better understand just how vulnerable are our oceans.

Sources

International Program on the State of the Ocean (IPSO), in conjunction with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), State of the Ocean Report 2013: Perils, Prognoses and Proposals, consisting of five reports. www.stateoftheocean.org/research.cfm

The five reports are:

Bijma, J., et al. “Climate change and the oceans – What does the future hold?” Mar. Pollut. Bull. (2013),

Ateweberhan, M., et al. “Climate change impacts on coral reefs: Synergies with local effects, possibilities for acclimation, and management implications.” Mar. Pollut. Bull. (2013), dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.011

www.stateoftheocean.org/pdfs/Ateweberhan-et-al-2013.pdf

Gjerde, K.M., et al. “Ocean in peril: Reforming the management of global ocean living resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction.” Mar. Pollut. Bull. (2013), dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.07.037

www.stateoftheocean.org/pdfs/Gjerde-et-al-2013.pdf

Hutchinson, T.H., et al. “Evaluating legacy contaminants and emerging chemicals in marine environments using adverse

outcome pathways and biological effects-directed analysis.” Mar. Pollut. Bull. (2013),

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.012

www.stateoftheocean.org/pdfs/Hutchinson-et-al-2013.pdf

Pitcher, T.J., Cheung, W.W.L. “Fisheries: Hope or despair?” Mar. Pollut. Bull. (2013), dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.05.045

www.stateoftheocean.org/pdfs/Pitcher-Cheung.pdf

See also: Alex D. Rogers and Dan Laffoley, Introduction to the special issue: The global state of the ocean; interactions between stresses, impacts and some potential solutions. Synthesis papers from the International Programme on the State of the Ocean 2011 and 2012 workshops. www.stateoftheocean.org/pdfs/Rogers-Laffoley-2013.pdf

The Economics of Ecosystems & Biodiversity (UN), Why Value the Oceans – A Discussion Paper (2012), with Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Enviornmental Policy. www.teebweb.org/wp-content/uploads/Study%20and%20Reports/Additional%20Reports/TEEB%20for%20oceans%20think%20piece/TEEB%20for%20Oceans%20Discussion%20Paper.pdf

John Upton, “Greens sue EPA over Pacific Northwest’s increasingly acid waters,” Grist (17 Oct 2013).

grist.org/news/greens-sue-epa-over-pacific-northwests-increasingly-acid-waters/

No comments yet, add your own below