Background

In two new reports, the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) assesses how the use of onshore wind, principally for generating electricity, and bioenergy, or biomass, for heat can transform Ireland to a lower carbon economy and impact the wider economy. The reports are: A Macroeconomic Analysis of Onshore Wind Deployment to 2020 and A Macroeconomic Analysis of Bioenergy Use to 2020. Reliance on these renewable energy technologies —wind and biomass — will help Ireland to meet its legally binding EU renewable energy targets for 2020 of 12% renewable energy sources (RES) for heat and 40% for electricity. This transition by 2020 will also reduce dependence on imported fossil fuels, and reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs).

While it used to seem like a no-brainer to embrace wind and biomass, there are concerns about visual and other impacts from wind turbines and associated grid pylons, and from displacement of food sources, so SEAI’s analysis is useful to show us how besideshelping us reach climate targets, there are benefits to the wider economy from wind and biomass.

SEAI employed a Macroeconomic Sustainable Energy Economy Model (SEEM) based on a leading tool from the United States and adapted for Ireland by SEAI. The system relies on estimated total net employment, which unlike other systems, accounts for any loss of employment from changes in prices or displacement of existing activities. Data sets used include information on the structure of the Irish economy and population demographics. The employment gains take into account anticipated investment from 2013 to 2020, as well as changes in prices, income and output in the wider economy.

Wind Deployment

In 2013, Ireland had about 1.8GW of installed wind generation capacity that supplied 16.3% of its electricity. Interestingly, this represents the 12th highest level of installed wind capacity in Europe, and 4th highest in contribution to national electricity demand, ahead of Germany. To meet its 2020 target, installed capacity will need to grow to 3.56 GW of onshore wind energy. That growth will require capital investment in power plants, labour and operation costs of about €192 million annually.

SEAI notes that because Ireland does not rely significantly on coal or gas, and imports its oil, there will not be any displacement of indigenous energy sources. While noted in passing this fact has critical political implications for easing the transition to low carbon energy. As we see in the United States, Canada, Australia and elsewhere, enormous sums of money and political influences are being expended by the indigenous energy companies, notably oil and coal, to fight any efforts towards a low carbon economy. That particular opposition is relatively absent in Ireland.

The contribution to Ireland’s employment base, through wind deployment, will not be from heavy manufacturing of blades or towers, but instead it will be in indigenous skills in feasibility, planning, foundations and engineering expertise, as well as other service sectors such as law and accounting. In addition, preliminary design and operational maintenance of the electricity grid will boost local jobs.

SEAI acknowledges it has not included in its assessment the impact of more wind farms on the amenity values of surrounding areas, house prices, or tourism, nor whether such impacts will be positive or negative. At the same time, SEAI does not consider the impact of community-owned wind farms.

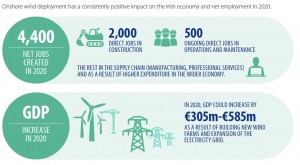

SEAI projects that by 2020 there will be a net increase of 4,400 jobs for building new wind farms and expanding the electricity network. In addition to these direct employment increases, if long-term costs of electricity are lowered, as expected, there will be greater competiveness among producers and greater household consumption. This additional disposable income from lower fuel bills will in turn generate more jobs in health, retail and accommodation/food services.

GDP could increase in 2020 by €305m to €585m. And of course the cost of imported fossil fuels will fall, by about €177m in 2020.

Biomass

While SEAI points out the possibilities of biomass to generate renewable electricity, any net employment benefits are available only if energy crops are sourced in Ireland, with anticipated potential net growth of 1,500 jobs in 2020. But if biomass is imported, and electricity prices rise to support energy feed-in tariffs from biomass, there would be a loss of jobs. In addition, using biomass for electricity would make it less available for heat.

In contrast, using biomass for heat is where the real benefits are realized. Using the same SEEM model, and datasets, SEAI projects that using biomass for heat will have similar benefits as wind in meeting Ireland’s EU obligations, reductions in imported fossil fuels, with related financial gains and reductions in CO2 emissions. SEAI does not include impacts in transport sector in its analysis.

Biomass will account for 13% of renewable electricity by 2020, which in turn represents 5% of the total electricity generated in Ireland.

The five categories of using biomass for renewable electricity are: (i) solid biomass combined heat and power (CHP); (ii) anaerobic digestion (AD) CHP; (iii) biomass co-combustion; (iv) biodegradable municipal solid waste (BMSW), or incineration); and, (v) landfill gas (LFG).

The wider impacts involve an increase in GDP of 0.14% to 0.17% in 2020, a growth of from €285m to €340m. Switching to lower cost biomass fuel will reduce production costs, lower consumer prices, and lead to reinvestment of these savings in the wider Irish economy. Net jobs are projected to increase by 2,750 in 2020, but critically if biomass is grown and sourced locally, jobs will double to 5,500.

SEAI is clear that the key step in these benefits comes from the conversion of oil-based boilers to biomass boilers in the industrial sector, as well as the local sourcing for the biomass.

Conclusion

With lots of opposition to wind and biomass, SEAI usefully points out that both wind and biomass can, indeed must, help Ireland meets its legally binding EU renewable energy targets for 2020, reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, and reduce GHGs. At the same time SEAI demonstrates that beyond these energy policy benefits, wind and biomass can deliver increased net jobs and macroeconomic benefits. Those considerations need to be part of any dialogue on wind and biomass sources of energy in Ireland.

Sources

Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI), A Macroeconomic Analysis of Onshore Wind Deployment to 2020: An analysis using the Sustainable Energy Economy Model (June 2015). www.seai.ie/Publications/Statistics_Publications/Energy_Modelling_Group_Publications/A-Macroeconomic-Analysis-of-Onshore-Wind-Deployment-to-2020.pdf

Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI), A Macroeconomic Analysis of Bioenergy Use to 2020: An analysis using the Sustainable Energy Economy Model (June 2015). www.seai.ie/Publications/Statistics_Publications/Energy_Modelling_Group_Publications/A-Macroeconomic-Analysis-of-Bioenergy-Use-to-2020.pdf

No comments yet, add your own below