Google, Corine, Landsat, Spot,

GeoEye and Lidar

This presentation reviews the implications of the work undertaken for Friends of the Irish Environment in UCC’s Department of Geography and Coastal and Marine Resources Centre’s Draft Report on ‘the Use of Remote Sensing to Evaluate thepotential of Identifying Exposed and Vegetated Peatlands in Ireland in the context of the developing science of Earth Observation.

This presentation reviews the implications of the work undertaken for Friends of the Irish Environment in UCC’s Department of Geography and Coastal and Marine Resources Centre’s Draft Report on ‘the Use of Remote Sensing to Evaluate thepotential of Identifying Exposed and Vegetated Peatlands in Ireland in the context of the developing science of Earth Observation.

May I suggest that I am uniquely qualified to speak today about Remote Sensing – or Earth Observation [EO] – as one of the few human beings to have seen the very first satellite, Sputnik 1, hours before it plunged to a fiery death on 4 January, 1958.

I was a schoolboy in northern New York State and our inspired science teacher had made the school part of the International Geophysical Year ‘Moonwatch’. This was a network of 200 observation posts across the world that were trained to observe the early satellites in what was then described as ‘the largest single scientific undertaking in history’. My school mates had before my time ground the lens and made the telescopes.

We were the ones who got to freeze in the pre-dawn practices; I can remember crying from the pain trying to defrost my hands in the bathroom one early dawn. But of the contingent of boys on duty that night, it was my scope that the bright little satellite chose to pass through.

50 odd years on, I have become involved in EO through Friends of the Irish Environment because we needed it for environmental monitoring. What I propose to try and outline today is why we needed remote sensing and what we have discovered about this tool.

Why our NGO needed remote sensing

FIE was alerted to the wide scale extraction of peat adjacent to the River Inny in County Westmeath by a contact operating through an anonymous internet address. This is a sample of the photographs he sent us.

We were also informed that the scale of these operations was even greater than that shown, involved several counties, various operators (we subsequently found these included cross-border interests and Anglo Irish Bank).

We were also informed that the scale of these operations was even greater than that shown, involved several counties, various operators (we subsequently found these included cross-border interests and Anglo Irish Bank).

These operations are part of a wide scale export of peat for wholesale horticulture to the south of England and Holland, and as a sorbent for industrial spills to Mozambique, South Africa. Michael Martin described the product as ‘environmentally friendly’ in a trade mission to Africa.

We visited the site.

We saw pumps exiting directly into the River Inny with peat-laden waters.

We saw pumps exiting directly into the River Inny with peat-laden waters.

We wrote to all local authorities in Ireland, asking for their records of peat extraction. There were virtually none. The Senior Executive Officer of Leitrim County Council spoke for them all when he informed us that planning ‘exemptions are very generous. A site of less than 10 hectares is exempt and a site larger than 10 hectares is exempt if work had begun prior to the coming into force of the Exempt Development Regulations 2001.’ The Leitrim SEO continued: ‘The Planning Authority does not have, not is it required to have, any records of the amount of peat extracted in the County. Neither does it have any details of the areas wherein peat extraction, by way of exempt development, is being undertaken.’

We were reminded of the terms of the ECJ judgment delivered in 1999 under the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive: “Ireland has not denied that no project for the extraction of peat, covered by point 2(a) of Annex II to the Directive, has been the subject of an impact assessment, although small-scale peat extraction has been mechanised, industrialised and considerably intensified, resulting in the unremitting loss of areas of bog of nature conservation importance. [C-392/96]”

We were reminded of the terms of the ECJ judgment delivered in 1999 under the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive: “Ireland has not denied that no project for the extraction of peat, covered by point 2(a) of Annex II to the Directive, has been the subject of an impact assessment, although small-scale peat extraction has been mechanised, industrialised and considerably intensified, resulting in the unremitting loss of areas of bog of nature conservation importance. [C-392/96]”

It was perhaps this judgment that led to the inclusion of ‘related drainage’ in the definition of peat extraction in the 2001 Regulations. Under S.I. no 538 of 2001 a new or extended area of over 30 hectares requires an EIA if it is may have significant impacts on a Natura 2000 site, alone or in combination with other activities. IPPC Licences require an EIA if the activity involves a new or extended area of over 50 hectares. A Discharge Licence also requires appropriate assessment in these circumstances. Cumulative impact must be considered.

In addition to adverse impacts on listed interests for nature conservation, extraction of peat and the consequent siltation of water with its dissolved organic carbon can be the cause of public health problems in potable water supplies.

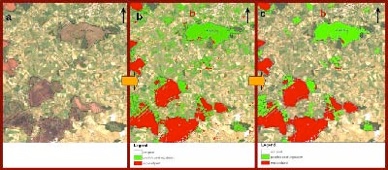

We suspected from Google Earth that we should be able to identify peatlands with ongoing extraction. Here is this landscape from Google Earth

We suspected from Google Earth that we should be able to identify peatlands with ongoing extraction. Here is this landscape from Google Earth

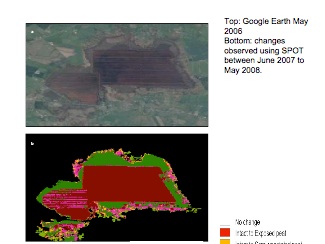

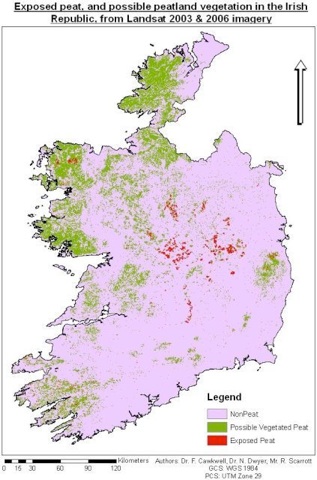

Would remote sensing technology enable us to create a map of the amount of peat being extracted in each County – the exposed peatlands of Ireland? We prevailed upon Dr. Fiona Cawkwell and her colleagues who undertook to produce a national scale map of exposed peatlands with a greater scale regional study.

Freely available imagery from LANDSAT was to be used for the first, and SPOT [the French Systeme Pour l’Observation de la Terre] imagery was to be sourced with an educational discount, giving higher resolution for the second.

There is a huge amount of satellite data in Ireland. Vast stocks of satellite images are held by Local Authorities relating to planning and EIAs – often in boxes marked ‘hard drives 2002’. The EPA, the OPW, the GSI, the National Biodiversity Centre, the NPWS, Teagasc, and semi states like Coillte, Bord na Mona and the ESB all hold geoinformatics data.

Thirteen of the 20 third-level institutions have schools or Departments holding geoinformatics information. These come under a variety of headings – civil engineering, chemical and life sciences, geography, botany, geology, and environment. At UCD, no less than 5 schools, 2 departments, 1 institute and 1 research group all hold geoinformatics, with DIT Spatial Planning including ‘spatial data research.’

The data is sourced from a variety of satellites which vary in the sensors they carry and the width of the swatch they cover. Additional images are sourced from aerial photography. Laser-based contour mapping is becoming more common, with a new Irish national survey recently announced. These systems, also known as LIDAR, are based on a downward-pointing laser placed on an aircraft. Because of its three dimensional image it is alone amongst the remote sensors in being able to distinguish between hand-cut, milled, and uncut bog surfaces.

Landsat – which we used – would be familiar to most people as it formed the basis of Google Earth. Its base imagery is 30m and it is multispectral – various raw bands provide different data. However, Google is actively replacing this base imagery with higher resolution datasets based on 2.5m SPOT imagery.

Each of the satellites offers different resolution and spectrum, from Landsat’s 30 metres [Landsat also has 15m data] to SPOT’s combination of 10m and 5m down to more specialised and expensive very high resolutions. Each higher resolution is not only more expensive per image but means the swathes are narrower resulting in more images and costs in processing and classification.

Satellites that provide higher resolution may have to be balanced against more limited multispectral bands. In our case only SPOT images within the summer growth months provided sufficient clarity to distinguish between the characteristic plant communities because of the limited bands compared to LANDSAT.

But the most significant problem in using satellite observation for environmental monitoring in Ireland is cloud cover. Cloud, cloud shadows, and simply the moisture in the air can distort the information. LANDSAT shuts down the camera when there is more than 5% cloud cover.

An analysis of the Landsat images of the Boora area in the years 1990 – 1996 showed that there were less than two cloud free scenes per year acquired by Landsat. If the need for the images is in the summer when the vegetative differences are most pronounced and vegetative discrimination easiest, the availability of suitable images is further reduced.

It will sadly come as no surprise that there were no cloud free images over the past three Irish summers that could be used for our map. The necessary 8 images had to be sourced over a three-year period 2003 – 2006 and all from different seasons.

It will sadly come as no surprise that there were no cloud free images over the past three Irish summers that could be used for our map. The necessary 8 images had to be sourced over a three-year period 2003 – 2006 and all from different seasons.

Then, there is the way the information is digitally processed to show what you want. CORINE – the EU land use map – for example, does not distinguish between exposed peat and vegetated peat, although it holds the data to do so.

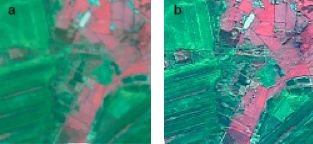

The EPA is currently running a pilot programme that seeks to recreate Fosset’s Habitats of Ireland using ‘Definies’ image segmentation software as a classification tool, a rule-based classification process with software that uses homogenous groups of pixels to form landscape units. This project is using three sets of imagery from different growth seasons as this is the best way of differentiating between different plant communities. Plant communities show different characteristics at different times of the year, so two communities that look quite similar in spring can be differentiated by looking at their characteristics in Autumn, for example.

Digital image processing provides an objective and repeatable way of ‘training’ through the creation of rule-sets based on spectral characteristics. But it is not so easy: a land cover training data set developed for one of our map’s eight original segments could not be applied to another segment as the season was different. ‘Post processing’ or ‘cleaning’ and ‘cloud masks’ can further clarify images.

Two key factors are currently holding back the use of EO in environmental monitoring.

Two key factors are currently holding back the use of EO in environmental monitoring.

This first is the limited number of GIS trained graduates capable of assessing the various sources of remote data, selecting and operating the most appropriate software, and producing final images that are fit to purpose and presenting them, when necessary, to judges and juries in language they can trust.

The second is the cost and availability of the data.

There is no common searchable database covering all major suppliers at this time. A 10-year international initiative has begun in Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS). At the moment, potential users have to access individual distributor’s warehouses and these are not designed with non-technical people in mind. Nor do they archive all data – some contain only images distributors think people will buy, favouring cities over rural areas. Some are only vaguely dated.

On the other side, NASA’s globe software and Landsat are works created by an agency of the United States government and as such are in the public domain at the moment of creation. The GeoEye Foundation provides commercial satellite imagery to students and faculty at select educational institutions and it also offers select imagery to support non-governmental institutions in their missions of humanitarian support.

Unfortunately, the cost of much of this data in Ireland is set at commercial rates by the Ordinance Survey Office while in the United Kingdom recent advances have made much of this data more freely available.

The best quality spatial data on river and stream systems in Ireland, for example, is that held by the EPA. It is based on river lines collected by OSI, with some improvements and a large amount of added attribution. Due to this, this data can only be given to holders of a license for the OSI Discovery Series vector water lines data.

Even with the data obtained, the legal basis for its use is only now evolving.

EO is emerging slowly in legislation and guidelines around the world. Ray Purdy is undoubtedly the world’s expert on EO and the law. He draws attention to New South Wales, Australia, where illegal vegetative clearance was a serious issue. Since EO’s entry into legislation ten years ago, there have been dozens of prosecutions; an official told Purdy that ‘without satellite imagery to target potentially unlawful clearing and use as evidence there would be little if any vegetative compliance in Queensland.’

The Environmental Law of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has now authorized the use of satellite remote sensing to ‘conduct the analysis, comparison and verification of environmental pollution sources and deterioration’. ‘Remote sensing shall be used as a surveillance tool to detect polluters and to substantiate liability claims’. An environmental monitoring programme, initiated last month, covers all four environmental domains “land – air – coast – marine”.

Malaysia officials are preparing amendments to their legislation to allow the use of EO in Court as a result of their success with the targeted enforcement strategy of the Malaysia Forestry Department. They recently contracted with SPOT for weekly images of sensitive areas (those with high potential for forest clearing). These are sent to a ground receiving centre, processed within six hours, and the data then placed in their database which is linked to the department. To access any information, the department accesses the database and calls up the specific page to check if logging carried out in that area is legal. Until the legislation is enacted, Inspectors go down to the field to check and use their report as evidence in Court.

At the other extreme, the residents of Mumbai in India recently provided an example of the individual use of EO. After their complaint against encroachment in a mangrove area fell on deaf ears, the resident of the Dahisar suburbs of Mumbai in India collected money to buy before-and-after aerial images to prove their point and fight their case in court.

Forum member Dr S P Mathew is quoted in the Mumbai News as saying: “We approached the Indian Space Research Organisation, IIT-Mumbai, and even Google for images of the area, but were unsuccessful. Then, after six months of research, we found a US company called Mapmart which could provide high resolution images, and struck a deal for US $600. We think we’ll be the first in Mumbai to use such a method.”

Forum member Dr S P Mathew is quoted in the Mumbai News as saying: “We approached the Indian Space Research Organisation, IIT-Mumbai, and even Google for images of the area, but were unsuccessful. Then, after six months of research, we found a US company called Mapmart which could provide high resolution images, and struck a deal for US $600. We think we’ll be the first in Mumbai to use such a method.”

Where EO is irreplaceable is with the monitoring of isolated regions and areas where for political or physical reasons access is difficult and its use by NGOs is advancing in addressing environmental exploitation, human rights abuse, and refugee conflicts.

Grasberg’s Freeport mine in Irian Jaya (West Papua) is a strong contender for the worst case of environmental and human rights abuse of any mining project currently underway in the world. It comprises several delicate ecosystems – alpine meadow, wetland and mangrove forest – which make this environmental site world-renowned for its range and diversity of flora and fauna. This mine is the largest gold mine in the world and the third largest copper mine.

Grasberg’s Freeport mine in Irian Jaya (West Papua) is a strong contender for the worst case of environmental and human rights abuse of any mining project currently underway in the world. It comprises several delicate ecosystems – alpine meadow, wetland and mangrove forest – which make this environmental site world-renowned for its range and diversity of flora and fauna. This mine is the largest gold mine in the world and the third largest copper mine.

The recent deaths of two U.S. journalists and the West Papuan leader, Kelly Kwalik, in late December 2009 made access more difficult. Recently satellite data has been used to monitor rain forest “conversion” and land use planning. The level of detail allows for the monitoring of individual trucks (8 yd x 16 yd- width x length) and the ability to differentiate the operations of different types of mine machinery.

The recent deaths of two U.S. journalists and the West Papuan leader, Kelly Kwalik, in late December 2009 made access more difficult. Recently satellite data has been used to monitor rain forest “conversion” and land use planning. The level of detail allows for the monitoring of individual trucks (8 yd x 16 yd- width x length) and the ability to differentiate the operations of different types of mine machinery.

Multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) have been an encouraging sign of international commitment to protect the environment. But many international laws in fact lack compulsory inspection regimes (or standards for those inspections) or sufficient resources to ensure compliance.

These are obvious targets for EO. There is a basis in EU inspection regimes for farmers, which specify that farmer’s selected for audits require 80% ‘on the spot check by remote sensing’; the Commission spends €5 million a year acquiring images to deal with its 50 million land parcels.

EO evidence can be questioned on the basis of its credibility or reliability. Processing could conceivable add an element of hearsay. Audit trails might be sought. But in fact, the bull may already be in the yard in that satellites are being used for compliance monitoring and enforcement without, Purdy suggests, prescription under legislation.’

A further argument for expressly prescribing satellite monitoring by law is to ensure that its application does not interfere with a person’s private life under a country’s constitution or agreements like the European Convention on Human Rights.

Even without legal grounding, there is nothing to stop local authorities requiring high quality EO images of application sites and conditioning these to be updated annually. Nor has FIE yet met any barriers to the targeted enforcement strategy using EO that we are pursuing with our partners.

Chester Bowles perhaps provides the best rational for ‘the spy in the sky’ in writing about his years in public life as an American politician and diplomat:

‘20% of the regulated population will automatically comply with any regulation. 5% will try and evade it, and the remaining 75% will comply as long as they think the 5% will get caught and punished.’

NOTES

Draft report on ‘The Use of Remote Sensing to Evaluate the Potential of Identifying Exposed and Vegetated Peatlands in the Republic of Ireland’, Produced by Dr. F. Cawkwell, UCC; March 2010, for Friends of the Irish Environment, unpublished.

FIE is indebted to Ian Lumley, the Heritage Officer of An Taisce, who identified this trade and has pursued the issue doggedly. In particular, his success in preventing planning permission for extraction to be granted to permit the sale to Erin Horticulture of the NPWS-owned 80h Kilballyskea Bog in Shinrone, County Offally [ABP RF1078] is a case worth reading. The Department had been intending to use the largely degraded raised bog [‘unworthy of conservation’] to relocate displaced peat producers from bogs that were designated conservation areas in the locality. When this did not happen, they offered the bog for public sale. The Board refused inter allia because ‘The proposed development would adversely affect an Annex I habitat type: ‘degraded raised bog still capable of natural regeneration’. www.friendsoftheirishenvironment.net/cmsfiles/files/library/abp_r225687.pdf

Discharges licences are listed in part II of S.I. No. 94/1997:EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (NATURAL HABITATS) REGULATIONS, 1997 as an ENACTMENT REFERRED TO IN REGULATION 32. Reg 32: (1) Where an operation or activity or an established activity to which an application for a licence or a revised licence or a review of a licence or revised licence, as appropriate, under any of the enactments set out in Part II of the Second Schedule applies is neither directly connected with nor necessary to the management of a European site but likely to have a significant effect thereon either individually or in a combination with other operations or activities or established activities a local authority, the Board or the Environmental Protection Agency shall ensure that an appropriate assessment of the environmental implications for the site in view of the site’s conservation objectives is undertaken.

Bord na Mona is exempt from the provisions of the Water Pollution Acts, a fine example of parallel legislation over which FIE has protested to no avail. Section 27 of the Turf Development Act 1945 gives immunity to Bord na Mona’s operations from the Local Government (Water Pollution) Acts. The Minister is only required to take such measures to protect the environment if taking ‘such precautions and making such provisions will not cause substantial detriment to the works or substantial hindrance to, or substantial increase to the cost of, the works’.

Dissolved organic carbon reacts with chlorine to produce trihalomethanes, cancer-causing agents which were identified as a major problem in 51 of Irish drinking water supplies in 2007. [EPA, Drinking Water in Ireland 2007] Their removal requires separate treatment and costs that should be borne by the polluter, not the State.

The support of the Department of Environment’s Spatial Planning, and COMHAR, the National Sustainability Council, with encouragement from the National Biodiversity Centre, made the pilot project possible.

‘Existing Geo-informatics in the Republic of Ireland’, Rory Scarrott, for Friends of the Irish Environment, unpublished, 2010. www.friendsoftheirishenvironment.net/cmsfiles/files/library/geoinformatics_report.pdf

The Irish town of Westport was added to Google Earth in 3D on January 16, 2008. and is the first such model of an Irish town to be created. As it was developed initially to aid Local Government in carrying out their town planning functions it includes the highest resolution photo-realistic textures to be found anywhere in Google Earth. [Source: Google Earth.]

In this context Dr. Cawkwell notes in her conclusion to the FIE Report: ‘With additional funding it would be interesting to explore the potential of TerraSar-X imagery, the highest spatial resolution microwave images available and equivalent to the SPOT multispectral images used in this project. Being a microwave imager cloud cover would not be an issue, permitting a wider range of images to be suitable, and although unable to distinguish vegetation species the differences in backscatter between exposed, semivegetated and intact peat surfaces may be sufficient to identify regions of change on a more frequent basis than can be realistically anticipated from high resolution optical imagery.’ TerraSar-X is radar based, and so can operate independent of cloud cover and during the hours of darkness with a definition of up to 1m.

Jason Larkin, EPA, email, 01.07.09: IE-EPA-2008-GIS-FA Remote Sensing/01. ‘Suitability of a rule-based feature extraction and classification processing methods to a habitat mapping solution for a study area in Ireland.’

Free-gis-data.blogspot.com (2010) is an excellent site where you can find complete information about websites which provide free GIS, Remote Sensing, spatial and hydrology data as a service.’ Op cite. Existing Geo-informatics in the Republic of Ireland useful for monitoring landcover and landuse changes impacting on peat soils and water quality’

It was only after I submitted my title for this paper that the conference organiser, Owen McIntyre – and then a fellow contributor, Andrew Jackson – kindly sent me the recent paper by Ray Purdy, ‘Using Earth Observation Technologies for Better Regulatory Compliance and Enforcement of Environmental Laws’. See UCL FACULTY OF LAWS, Centre for Law and the Environment, www.ucl.ac.uk/laws/environment/index.shtml?research_main. Accessed 4 April, 2010.

jel.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/22/1/59

www.mumbaimirror.com/index.aspx?page=article§id=2&contentid=2010031020100310040110234a9ae6fa1. Mumbair Mirror March 10, 2010. Accessed 4 April, 2010

High Resolution Satellite Imagery for Monitoring Environmental and Climate Induced Change in Isolated Rural Communities, by Dr. Christopher Lavers , Britannia Royal Naval College www.directionsmag.com/article.php?article_id=3457, accessed 4 April, 2010.

To show how savings may be affected, Purdy quotes The British Potato Council which changed over largely to satellite observation, reducing their field staff from 92 to 16 and so saving €3 million per annum.

‘Once a farmer has been selected for an on-the-spot check in accordance with paragraph 3, at least 80 % of the area for which he requests aid under aid schemes established in Titles III and IV of Regulation (EC) No 1782/2003 shall be subject to on-the-spot check by remote sensing’. Commission Regulation (EC) No 796/2004 of 21 April 2004, OJ 2004 L 141

Satellites – an new area for environmental compliance, Ray Purdy, 1996 www.ucl.ac.uk/laws/environment/satellites/docs/Rayscan003,%20JEEPLb.pdf [accessed 4 April 2010]

Chester Bowles, My Years in Public Life, 1974, quoted in Purdy, op cite. Purdy also quotes the 19th century English utopian Jeremy Bentham: ‘The more strictly we are watched the better we behave’.

Tony Lowes, Friends of the Irish Environment

The article is based on a presentation by Tony Lowes at Law and the Environment 2010, 8th Annual Conference, University College Cork in April 2010

No comments yet, add your own below