Introduction.

When change is necessary, it is necessary to change. It is a core responsibility of governments everywhere to manage those risks that cannot be managed successfully on their own by their citizens, communities, and enterprises. Amongst the most challenging of these risks is climate change, but they all face very daunting head winds as they seek to manage it.

The key arguments of the series of papers that follow in this issue of EAERE Magazine are that: we need to change how we manage climate change; one change worth serious consideration is for the four largest greenhouse gas emitters (China, the European Union, India and the US) to find ways that work to collaborate.

A key first step is understanding for all four their past performance as regards emissions and economic performance, and to explore possible future trajectories; this is provided by Sylvain Cail and Patrick Criqui. This first issue is devoted to the US. In the chapters that follow (author names in brackets) the following baseline information is provided: Climate Policy Architecture (Jack Lienke & Jason A. Schwartz); Domestic Climate Policy – looking back (Max Sarinsky); US Domestic Climate Policy – looking forward (Bethany A. Davis Noll); US Global Climate Policy – performance and prospects (Nat Keohane). The same template will be followed in successive issues as the baseline is established for China, the European Union and India. The series will be completed before the COP 26 in Glasgow (Nov 1-11, 2021) and a compilation will be available there.

We are not the first to use the word ‘deep’ in the climate policy context. The Deep Decarbonization Pathways initiative (DPPI) was a collaboration of leading research teams covering 36 countries. Their aim was to help governments and non-state actors make choices that put economies and societies on track to reach a carbon neutral world by the second half of the century. Their work showing the feasibility of doing what needs to be done was helpful in increasing the prospects for the Paris Agreement in 2015. Note 1. A recent paper from the US partner in DPPI (Williams et al, 2020) argues as follows: “Modelling the entire U.S. energy and industrial system with new analysis tools that capture synergies not represented in sector‐specific or integrated assessment models, we created multiple pathways to net zero and net negative CO2 emissions by 2050….. . Cost is about $1 per person per day, not counting climate benefits; this is significantly less than estimates from a few years ago because of recent technology progress.”

Our proposition is that the prospects of these huge climate dividends being delivered will be greatly enhanced if the Big Four collaborate.

In this framing paper, we set the stage for what follows by addressing: why these four; the progress that has been made in recent years; the logic of deep collaboration by the four largest emitters.

Why these Four?

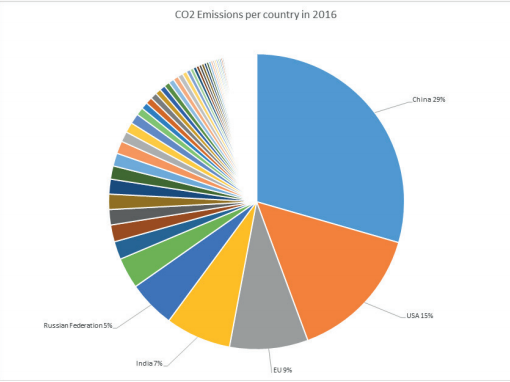

They contribute ~60% of total global emissions (Figure 1), account for about the same percentage of global GDP, and are home to close to half of the world’s population. Together, they have enormous resources, influence, and talents. If they succeed, we all succeed. But why not just two? China and the US together account for >40% of emissions; they on their own could also be potentially hugely influential as a ‘climate club’. There are many reasons for maintaining the number of key actors to four, but a key strategic consideration is the gain in resilience that a larger group could deliver over time. With four, if one or two jurisdictions opt out, that would still leave 3 or 2 still willing to collaborate and sustain the effort. Another important consideration is that India represents in some sense inclusion of the interests of many people of low income (Camuzeaux et al 2020). The collaboration must be extended over time to others who are committed and can see mutual advantage in engaging and contributing. The emissions from the rest of the world are rising rapidly, and they too must also be a part of the solution; our case for a deep collaboration by the Big Four is a complement, not a substitute for action at UN and other levels.

Figure 1. CO2 by Jurisdiction, 2016

Source: World Bank (CO2 emissions (kt) | Data (worldbank.org)), which in turn have as their source Carbon Dioxide

Information Analysis Center, Environmental Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Tennessee, United States.

Recent Progress in Practise and Perception

At the political level, in “US Global Climate Policy – performance and prospects” Keohane recounts how, beginning at Copenhagen (COP15) in 2009, the US and China agreed on climate ambition, which was further re-enforced at the Obama-Xi summit in 2013, and culminated in the joint announcement of intended nationally determined contributions in November 2014. This so called “G2” agreement helped pave the way for success at the Paris COP in 2015 which brought developed, emerging and developing countries into the same tent. It also set an important precedent: bilateral cooperation by the two largest emitters of greenhouse gasses.

At the technical level, there has been progress in terms of lowering the costs of reducing emissions, exemplified by the rapid decline in the costs of solar power, to the point that, under certain circumstances, it is cheaper than fossil sources (Nemet, 2019). This is symptomatic of a wider wave of innovation that is also lowering the costs of wind power and of battery storage, which in turn is enabling the electrification of road transport under certain conditions. In all countries, this may deliver jobs and economic activity and act as a sort of counter point to current or prospective economic decline in the fossil fuel dependent regions.

There has been a parallel increased awareness of the costs of inaction and the fact that these costs may occur sooner than expected; this is exemplified by more intense weather events, more flooding, longer droughts and more extensive and longer lasting forest and brush fires. And our understanding grows concerning the links between climate change and economic and political dysfunction and how this is becoming manifest in migration patterns, especially from South to North.

At the energy and climate policy level, the Big Four have their own experiences to draw from, especially as regards what works to reduce emissions. A few examples: the member states of the EU have for many decades used very high indirect carbon taxes (in the form of excise duties) on transport fuels, which has had the effect of reducing emissions dramatically from the road transport sector compared to emissions from those jurisdictions which did not apply such taxes (Sterner, 2007); at EU level, car companies selling into the EU have to meet a fleet average emissions target which shrinks every year. Automatic fines are payable for non-compliance, [Note 2] and similar policies are already in place or in prospect in the US and China. The US has had considerable success at reducing emissions from the power sector as a result of innovation (fracking) which dramatically increased the competitive advantage of natural gas over fuel, and in parallel promoting renewables, whose share of the fuel mix has grown rapidly (Mohlin et al, 2018). Both China and India have similarly dramatically increased the supply of renewables.

The Case for Deep Collaboration

The following are arguments for them to consider.

1. Self-interest.

Climate change is happening, and if not managed successfully, is likely to be a huge disrupter within their respective borders, a destroyer of their physical and social infrastructure, life support systems and of the economic and social wellbeing of their peoples, a destroyer of prosperity in those countries with which they trade, a blighter of future prospects, and the trigger for a ‘blame game’: who refused to act while there was still time?

2. Psychology

It will be a huge reassurance for farmers in Burundi and shopkeepers in Brisbane to know that the Big Four are deadly serious about meeting the climate change challenge, and willing to collaborate to this end, thereby giving them a future.

3. Delivery of practical dividends with a sectoral focus:

In the case of climate policies upon which they have already embarked, they can learn from each other at sectoral level and take advantage of experience effects. Note 3. In “Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions from the Four Largest Emitters Globally [China, European Union (27+1), India and the US] – past performance and exploration of future scenarios” by Cail and Criqui, inter alia, they show the time series of CO2 emissions from 5 sectors – power (mainly electricity), transport (mainly road), industry, buildings, and process (mainly steel and cement). In all cases, the power sector is the largest emitter; transport ranks second in the US and the EU, third in India and fourth in China.

For each sector (which should include agriculture and forestry – because our data focusses mainly on CO2 emissions, we have not included this sector in our benchmarking, which is a weakness) the following sequence could be considered [Note 4], in each jurisdiction:

· A granular assessment of the policies already tried and those under consideration, and their performance, their key strengths and weaknesses, technically and politically

· The current policy ambitions and the challenges that implementation could pose

· The lessons from each jurisdiction that might be of relevance for one or more of the other three

· Potential for policy collaboration and an assessment of the value they could add in terms of increasing and/or accelerating climate ambition

If more than one decide that collaboration could yield substantial gains, they find a way that works for them to do so

An example: China, the EU and the US have set or will set mandatory standards for the carbon efficiency of car fleets sold into their jurisdictions; this policy is already accelerating the share of electric cars in new car sales, and it also provides an opportunity for hydrogen fuelled cars; India is also addressing the air pollution and climate challenges posed by its rapidly growing road transport sector and how best to manage the transition to a cleaner future. Applying the sequence above to this issue could, at a minimum, help some or all four of them individually to improve the design and delivery of this policy and, at a maximum, at least two of them could decide to act in concert. The result could be more total ambition, delivered sooner. The climate impact of electric vehicles depends fundamentally on the carbon efficiency of the power sector; finding ways to collaborate to accelerate carbon-reductions therein would be a logical next step.

4. Delivery of practical dividends with a policy instrument focus (Note 5)

The instrument menu is familiar, and some are already being applied, or in prospect, across sectors: it includes voluntary agreements, market-based instruments (carbon taxes and emissions trading), regulation, research and innovation, removing barriers, subsidies etc. The process template suggested above for application to sectoral policy could be similarly employed to the policy instrument mix. For many good reasons, most economists favour market-based instruments. In On American Taxation, Edmund Burke observed that: “To tax and to please, no more than to love and be wise, is not given to men”. This simple sentence goes far to explain why it has proved so difficult to convert this simple and seductive (to economists) proposition into action.

Thought Leadership

A lot of the thought leadership on policy instruments has been led by economists and political scientists. Because economists have a logical enthusiasm for carbon prices as the key, if not singular, instrument [Note 6], much of the recent discussion from the profession has focused on carbon taxes as the instrument of choice. The policy must however be global but who is to start. Research shows that climate treaties are hard to sustain and therefore we may need to start with action by groups, under the general heading of ‘climate clubs’ or a ‘climate compact’. If the group is large and powerful it can overcome the tendencies to free-riding that make treaties crumble. Nordhaus (winner of the Nobel Prize in 2018) has been a leading exponent of this analysis; his prescription is a club whose members “pay dues” through costly abatement with non-members penalized through tariffs. Such a club has the incentives to overcome free-riding. More detail on his thinking and supporting references are in the Annex.

This advocacy provides both a clear logic for action at this level (which we share) and a powerful single instrument to advance it. As regards the latter, our approach is more modest and more incremental, on the grounds that the first steps are often the hardest but most essential, requiring their own forms of quiet courage and skill, and acorns can grow into trees. In an Annex more detail is provided on the evolution of thinking across time on collective action at the interface between theory, evidence and finding ways that work in the world of now; this includes some of the references that inform that exciting and essential frontier. We apologise for the fact that this is at present exclusively ‘western’ (Europe and North America) in focus, an omission we plan to correct in time.

Conclusion

In human as well as business relationships, before they become ‘serious’, prospective partners often press the ‘pause’ button, and ask themselves the following sorts of questions: do I really know enough about the backstory and history of this person/company, what their real qualities and achievements are, how well they deal with adversity, the constraints they face, their willingness to make sacrifices in the short term to advance a longer term shared ambition, their ability to convert ideas into ambitious shared achievement, their willingness to share workload, evidence, and credit etc.? Our hope is that this series will begin to bring some clarity on some of these issues

We recognize that this is the easy bit. Finding ways that work to deliver outcomes is always hard, and there are huge competing agendas, some potentially very contentious and rancorous, that will make it challenging for all to sufficiently untangle the climate agenda from the others, and find the time and space to devote to it, and to take advantage of the considerable advantages that collaboration can provide. The Big Four are now committed to climate action (Carlsson et al, 2020) and 2021 which in some ways looks like a new dawn. Leonard Cohen wrote that “There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in”. We hope that this small step will help them make the most of it.

Notes

Note 1. Many of the country reports produced in early 2015 are available at: Deep Decrabonization Pathways Project [IDDRI] at bit.ly/3u4Ayf9 and there are also many activities continuing today at IDDRI which are managed by Henri Waisman.

Note 2. Recent developments are addressed by Joe Miller in: ‘VW posts €10 billion profit in pandemic ravaged year after late recovery,’ Financial Times, January 22, 2021.

Note 3. Arrow (1962, p. 156) was the first to formally test the hypothesis that “technical change in general can be ascribed to experience, that it is the very activity of production which gives rise to problems from which favorable responses are selected over time”

Note 4. And this could be broken down to sub-sectoral level – e.g., address common understanding of effective sectoral policies and the argument on learning curves for strategic technological components: wind turbines, PV panels, batteries, fuel cells, electrolysers for H2 etc.

Note 5. Sterner and Coria (2011) provide a comprehensive menu of policy instruments and an assessment of their performance in both developed and developing countries

Note 6. However, innovation is being added to the mix, and this is reflected by the fact that Nordhaus, the winner of the Nobel Prize for economics in 2018, included “Rapid technological change in the energy sector is essential” as one of the four steps in the concluding slide of his Nobel lecture (Nordhaus, 2018). The wider case for innovation as an instrument of climate policy is made by Convery (2021).

References

Arrow, Kenneth J. 1962. The Economic Implications of Learning by Doing Author(s): The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 29, No. 3, June pp. 155-173

Carlsson, F., Kataria, M., Krupnick, A., Lampi, E., Löfgren, Å., Qin, P., Sterner, T. & Yang, X. (2020). The Climate Decade: Changing Attitudes on Three Continents. Journal of Environmental Economics and Modelling

Camuzeaux, J., Sterner, T. and Wagner, G. (2020). “India in the coming climate G2?”. National Institute Economic Review, 251, R3-R12. DOI: doi.org/10.1017/nie.2020.2

Convery, Frank J, 2021. “Carbon-reducing innovation as the essential policy frontier – towards finding the ways that work”. Environment and Development Economics (forthcoming)

Mohlin K, Camuzeaux JR, Muller A, Schneider M and Wagner G (2018) Factoring in the forgotten role of renewables in CO2 emission trends using decomposition analysis. Energy Policy 116, 290–296

Nemet GF (2019) How Solar Energy Became Cheap: A Model for Low-Carbon Innovation. New York: Routledge.

Nordhaus, William D, 2018. Climate Change: the ultimate Challenge for Economics, Nobel Lecture, Stockholm, December

Sterner T, 2007. Fuel taxes: an important instrument for climate policy. Energy Policy 35 3194–3202.

Sterner, Thomas, and Jessica Coria, 2011. Policy Instruments for Environmental and Natural Resource Management, RFF Press.

Williams, James, H. Ryan A. Jones, Ben Haley, Gabe Kwok, Jeremy Hargreaves, Jamil Farbes, and Margaret S. Torn 2020. “Carbon‐Neutral Pathways for the United States”, AGU Advances, agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2020AV000284

This article was first published in the magazine, EAERE, Europian Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, n. 11 Winter 2021. drive.google.com/file/d/13ZZmVUAC-ZQrKOa3-KBfMI0pVHvu1wO2/view

The authors:

Frank J. Convery (frank.convery@envecon.eu) completed forestry degrees at University College Dublin and PhD (forestry economics) at the State University of New York, followed by careers at Duke University, Heritage Trust Professor at University College Dublin, and Chief Economist, Environmental Defense Fund. His professional passions: bringing academic research down to where things are done; finding ways that work to protect our shared climate and environmental commons with a focus on mobilizing markets and (latterly) innovation to these ends; help make Ireland and Europe exemplars thereof.

Thomas Sterner (thomas.sterner@economics.gu.se) is a leading environmental economist. His main work is on discounting, environmental policy instruments, and environmental policies in developing countries. Recent published research includes an update to the DICE model, Covid-19 and climate policy, and carbon taxation. He serves on several prominent boards, and is also frequently interviewed in media. He has been elected Visiting Professor at Collège de France, worked as Chief Economist at the Environmental Defense Fund and also been President of EAERE during 2008-2009.

No comments yet, add your own below